Regional Sustainability ›› 2021, Vol. 2 ›› Issue (3): 280-295.doi: 10.1016/j.regsus.2021.11.001cstr: 32279.14.j.regsus.2021.11.001

• Full Length Article • Previous Articles

Md. Habibur RAHMANa,b,*( ), Bishwajit ROYb,c, Md. Shahidul ISLAMb,d

), Bishwajit ROYb,c, Md. Shahidul ISLAMb,d

Received:2020-12-09

Revised:2021-08-09

Accepted:2021-11-04

Published:2021-07-30

Online:2021-12-24

Contact:

Md. Habibur RAHMAN

E-mail:habibmdr@gmail.com;rahman.habibur.66w@kyoto-u.jp

Md. Habibur RAHMAN, Bishwajit ROY, Md. Shahidul ISLAM. Contribution of non-timber forest products to the livelihoods of the forest-dependent communities around the Khadimnagar National Park in northeastern Bangladesh[J]. Regional Sustainability, 2021, 2(3): 280-295.

Table 1

Profile of sample villages around the Khadimnagar National Park (KNP)."

| Village | Household size (N) | Sample size (n) | Location and distance (km) | Forest dependency level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charagang Tea Estate (CTE) | 142 | 31 | Adjacent (0-1) | Moderate to high |

| Khadimnagar Tea Estate (KhTE) | 462 | 70 | Outside (1-2) | Moderate to high |

| Bajartal | 37 | 37 | Outside (2-3) | Moderate |

| Kalagul Tea Estate (KATE) | 247 | 40 | Adjacent (1-2) | Moderate to high |

Table 2

Demographic characteristics of the surveyed respondents."

| Parameter | Percentage of the respondents (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KhTE | CTE | Bajartal | KATE | Total | |

| Age range | |||||

| 16-30 years | 57.1 | 41.9 | 40.5 | 20.0 | 42.7 |

| 31-45 years | 28.6 | 38.7 | 40.5 | 62.5 | 40.4 |

| 46-55 years | 14.3 | 19.4 | 18.9 | 17.5 | 16.9 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 58.6 | 77.4 | 91.9 | 100.0 | 78.1 |

| Female | 41.4 | 22.6 | 8.1 | - | 21.9 |

| Family size | |||||

| 1-5 persons | 81.4 | 83.9 | 78.4 | 90.0 | 83.1 |

| 6-8 persons | 18.6 | 16.1 | 18.9 | 10.0 | 16.3 |

| >8 persons | - | - | 2.7 | - | 0.6 |

| Education (years of schooling) | |||||

| Illiterate and can only sign (0 year) | 32.9 | 35.5 | 32.4 | 40.0 | 34.8 |

| Primary (1-5 years) | 37.1 | 38.7 | 37.8 | 32.5 | 36.5 |

| Junior secondary (6-8 years) | 27.1 | 16.1 | 29.7 | 27.5 | 25.8 |

| Senior secondary (9-10 years) | 2.9 | 9.7 | - | - | 2.8 |

| Occupational categories (income source) | |||||

| Fuelwood collectors | 34.3 | 19.4 | 8.1 | 20.0 | 23.0 (P) |

| Farmers | 14.3 | 22.6 | 21.6 | 25.0 | 19.7 (S) |

| Small-scale businessmen | 4.3 | 12.9 | 21.6 | 22.5 | 13.5 (S) |

| Day labourers | 15.7 | 16.1 | 16.3 | 17.5 | 16.3 (S) |

| Tea estate labourers | 31.4 | 29.0 | 32.4 | 15.0 | 27.5 (S) |

Table 3

Basic information of available non-timber forest products (NTFPs) in the KNP."

| NTFP type | Usage pattern | Availability trend | Percentage of perception as NTFPs (%) | Reason for the observed trends | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of NTFPs collection | Current status | Status before co-management projects | ||||

| Bamboo | House-building materials, handicrafts, furniture, fuelwood, and vegetable | Moderate | +++ | ++ | 71.9 | Illegal bamboo harvesting has decreased due to forest patrolling under co-management projects. |

| Rattan | House-building materials, handicrafts, and furniture | High | +++ | ++ | 63.5 | Illegal rattan harvesting has decreased due to forest patrolling under co-management projects. |

| I. cylindrica | House-building materials (thatching materials of roof and shade), making brooms, fodder, and fuelwood | High | ++ | +++ | 57.3 | Due to increased plantation areas in denuded hills, the growing area has reduced. |

| Medicinal Plants | Curing different types of ailments | High | +++ | ++ | 48.9 | Over exploitation has decreased due to forest patrolling under co-management projects. |

| Tree poles | House-building materials, furniture, and fuelwood | Less | +++ | ++ | 51.1 | Illegal trees harvesting has decreased due to forest patrolling under co-management projects. |

| Fuelwood | Residential and commercial cooking, brick burning, and rice parboiling | High | +++ | ++ | 53.4 | Extensive fuelwood harvesting has decreased due to forest patrolling under co-management projects. |

| Fodder | Cattle feeding and fuelwood | High | ++ | +++ | 50.6 | Due to increased plantation areas in denuded hills, the growing area has reduced. |

| Wild fruits | Seasonal food for nutritional and medicinal purposes | Less | +++ | ++ | 51.7 | Over fruit collection has decreased due to forest patrolling under co-management projects. |

| Wild honey | Food for nutritional and medicinal purposes | Less | ++ | + | 48.3 | Illegal honeycomb harvesting has decreased due to forest patrolling under co-management projects. |

| T. maxima | Making brooms, fuelwood, fodder, and lime washing of building walls | Moderate | + | ++ | 43.8 | Due to increased plantation areas in denuded hills, the growing area has reduced. |

| Seasonal vegetables | Vegetables and curries food for nutritional and medicinal purposes | Moderate | +++ | +++ | 56.2 | Over harvesting has decreased due to forest patrolling under co-management projects. |

| Wildlife hunting and poaching | Food for nutritional and medicinal purposes, rituals for festivals, and illegally sale in the markets | Less | +++ | + | 80.3 | Illegal hunting and poaching have decreased due to forest patrolling under co-management projects. |

Table 4

Respondents’ attitudes towards NTFP collection and usage."

| Statement | Percentage of the respondents (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KhTE | CTE | Bajartal | KATE | Total | |

| Major types of NTFPs derived from the forest | |||||

| Fuelwood | 82.9 | 87.1 | 86.5 | 85.0 | 84.8 |

| Wild vegetables and fruits | 44.3 | 45.2 | 73.0 | 50.0 | 51.7 |

| House-building materials | 61.4 | 51.6 | 56.8 | 45.0 | 55.1 |

| Tree poles | 21.4 | 29.0 | 32.4 | 25.0 | 25.8 |

| Medicinal plants | 67.1 | 48.4 | 51.4 | 57.5 | 58.4 |

| Bamboo and rattan | 31.4 | 22.6 | 27.0 | 35.0 | 29.8 |

| Intensity of NTFP collection | |||||

| Daily | 58.6 | 45.1 | 32.4 | 32.5 | 45.0 |

| 3-4 times per week | 31.4 | 32.3 | 45.9 | 40.0 | 36.5 |

| Weekly | 10.0 | 22.6 | 21.6 | 27.5 | 18.5 |

| Time spent for NTFP collection per trip in the forest | |||||

| <3 h | 42.9 | 19.4 | 13.5 | 95.0 | 23.0 |

| 3-5 h | 51.4 | 80.6 | 81.1 | 5.0 | 72.5 |

| >5 h | 5.7 | - | 5.4 | 0.0 | 4.5 |

| Purposes of NTFP collection | |||||

| For own use | 34.3 | 45.2 | 32.4 | 25.0 | 33.7 |

| For sale in market | 37.1 | 35.5 | 40.5 | 45.0 | 39.3 |

| For own use and sale | 28.6 | 19.4 | 27.0 | 30.0 | 27.0 |

| Reasons for collecting NTFPs from the forest | |||||

| Available and free of cost | 87.1 | 83.9 | 75.7 | 87.5 | 84.3 |

| Don’t need much afford to collect | 57.1 | 67.7 | 64.9 | 75.0 | 64.6 |

| Other cooking fuels are expensive | 41.4 | 61.3 | 67.6 | 70.0 | 56.7 |

| Reactions regarding unavailability of NTFPs from the forest | |||||

| Unsustainable harvesting from the forest | 65.7 | 87.1 | 78.4 | 72.5 | 73.6 |

| Planting fuelwood and fruit-bearing trees | 54.3 | 58.1 | 51.4 | 82.5 | 60.7 |

| Buying from the market | 21.4 | 51.6 | 35.1 | 47.5 | 35.4 |

| Switching over to other available fuels | 30.0 | 29.0 | 21.6 | 30.0 | 28.1 |

| Don't know what to do | 14.3 | 22.6 | 32.4 | 32.5 | 23.6 |

Table 5

Respondents’ attitudes towards NTFP conservation and management."

| Attitude | Percentage of the respondents (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KhTE | CTE | Bajartal | KATE | Total | |

| Protection measures can conserve the forest resources | |||||

| Yes, the BFD and local people together can conserve | 65.7 | 51.6 | 54.1 | 62.5 | 60.1 |

| There is a need to implement the strict conservation zone | 14.3 | 22.6 | 21.6 | 22.5 | 19.1 |

| Restriction protection measures must be implemented | 20.0 | 25.8 | 24.3 | 15.0 | 20.8 |

| Impact of over-harvesting of NTFPs on forest ecology | |||||

| Significantly | 32.9 | 67.7 | 37.8 | 42.5 | 42.1 |

| Not significantly | 38.6 | 19.4 | 27.0 | 30.0 | 30.9 |

| No idea | 28.6 | 12.9 | 35.1 | 27.5 | 27.0 |

| Protected area can manage NTFPs in a sustainable way | |||||

| Yes, it can manage sustainably | 61.4 | 51.6 | 43.2 | 47.5 | 52.8 |

| No, the situation remains the same | 15.7 | 35.5 | 27.0 | 30.0 | 24.7 |

| No idea | 22.9 | 12.9 | 29.7 | 22.5 | 22.5 |

| Involvement of local people in NTFP management could improve the present stocks | |||||

| Agree | 77.1 | 71.0 | 78.4 | 80.0 | 77.0 |

| Disagree | 17.1 | 19.4 | 13.5 | 15.0 | 16.3 |

| Possibly | 5.7 | 9.7 | 8.1 | 5.0 | 6.7 |

| Increased NTFP collection could balance livelihoods and conservation in the protected area | |||||

| Positively | 85.7 | 87.1 | 89.2 | 80.0 | 85.4 |

| Negatively | 5.7 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 7.5 | 5.1 |

| No idea | 8.6 | 9.7 | 8.1 | 12.5 | 9.6 |

Table 6

Description of NTFPs collected from the KNP."

| NTFP type | Unit | Percentage of the respondents (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KhTE | CTE | Bajartal | KATE | Total | ||

| Twigs and branches (fuelwood) | Stake (1 stake=5 kg) | 27.1 | 22.9 | 25.7 | 24.3 | 39.3 |

| Tree poles (fuelwood+other uses) | Piece | 7.1 | 25.0 | 35.7 | 32.1 | 15.7 |

| Split wood (fuelwood) | Bundle (1 bundle=5 kg) | 34.0 | 28.0 | 22.0 | 16.0 | 28.1 |

| Bamboo (fuelwood+other uses) | Bundle (2-5 pieces) | 32.5 | 27.5 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 22.5 |

| Rattan | Bundle (5-10 pieces) | 27.5 | 30.0 | 32.5 | 10.0 | 22.5 |

| I. cylindrica and T. maxima | Stake (1 stake=5 kg) | 34.6 | 25.9 | 17.3 | 22.2 | 45.5 |

| Medicinal plants, seasonal fruits and seeds, fodder, and vegetables | - | 54.3 | 35.5 | 35.1 | 30.0 | 41.6 |

Table 7

Selling price of NTFPs and income earned from NTFPs."

| NTFP type | Selling price | Approximate income earned from NTFPs (USD/month) |

|---|---|---|

| Bamboo | 1.8-5.9 USD/culm | 11.8-14.2 |

| Rattan | 0.9-2.4 USD/culm | 5.9 |

| Twigs, branches, and split woods | 2.1-2.9 USD/bundle | 17.7-23.6 |

| Tree poles | 3.5-5.9 USD/m3 | 9.4-11.8 |

| Seasonal fruits | 3.5-5.9 USD/basket | 5.9-11.8 |

| I. cylindrica and T. maxima | 3.5-5.9 USD/bundle | 5.9-11.8 |

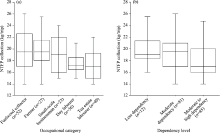

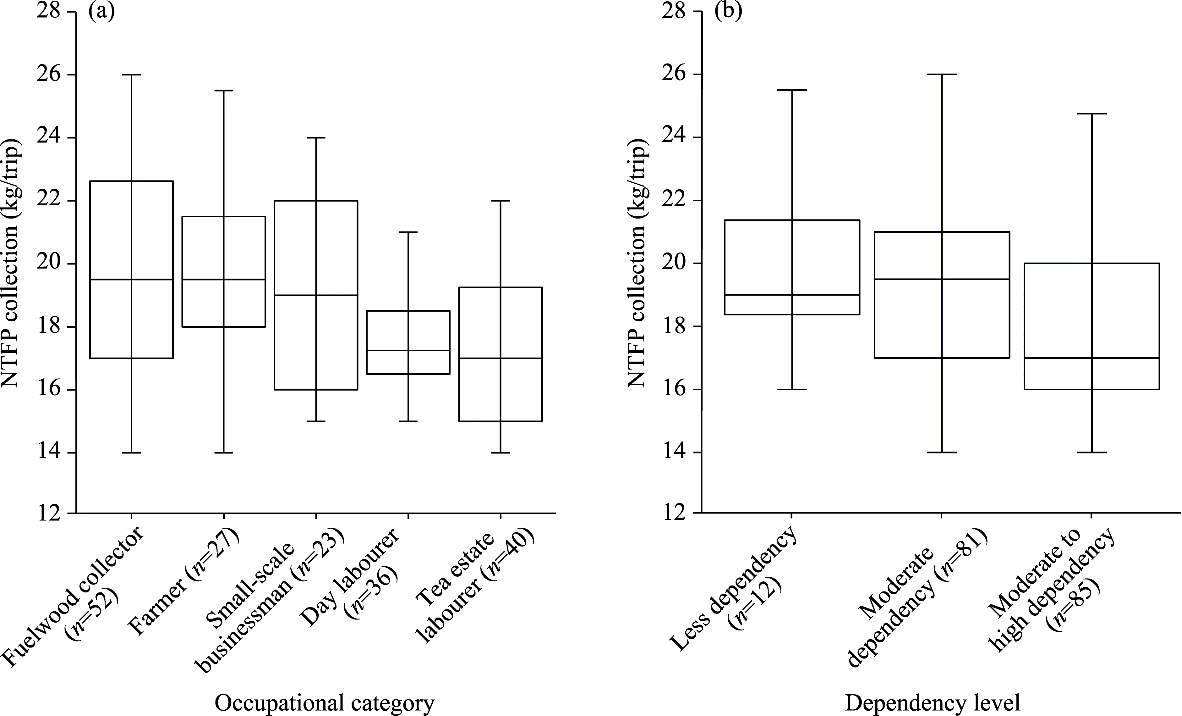

Fig. 3.

Relationships between the amount of NTFP collection per trip and different occupational categories of the surveyed respondents (a), and between the amount of NTFP collection per trip and various dependency levels of the surveyed repondents (b). The three lines in each box from bottom to top indicate the 25th percentiles, the median, and the 75th percentiles, respectively, with ±1.5×interquartile range as whiskers. n means the number of the respondents."

Table 9

Occupation-wise monthly income from NTFPs for the surveyed respondents."

| Occupational category | Average monthly income from NTFPs (USD) | Contribution to household income (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KhTE | CTE | Bajartal | KATE | Mean | ||

| Tea estate labourers | 28.8 | 28.3 | 25.7 | 18.0 | 26.1 | 58.4 |

| Fuelwood collectors | 24.2 | 22.0 | 26.6 | 26.8 | 24.6 | 55.0 |

| Day labourers | 28.2 | 34.4 | 19.0 | 21.1 | 25.7 | 61.4 |

| Farmers | 26.3 | 22.4 | 16.0 | 16.1 | 20.8 | 51.3 |

| Small-scale businessmen | 30.7 | 21.4 | 21.9 | 23.3 | 40.3 | 58.3 |

| Mean | 26.5 | 26.6 | 22.2 | 21.2 | 24.4 | 56.9 |

Table 10

Bivariate relationships between socio-demographic factors and household income from NTFPs."

| Socio-demographic factor of the respondents | r value |

|---|---|

| Age | -0.134 |

| Gender | 0.140 |

| Years of schooling | -0.009 |

| Family size | 0.175* |

| Time spent for NTFP collection | 0.300** |

| Distance between household and forest | -0.195** |

| Off-farm income | 0.172 |

Table 11

Regression analysis of relationships between influencing factors and annual income from NTFPs."

| Influencing factor | β value | Standard error | t value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time spent on NTFP collection | 0.057** | 0.025 | 2.231 |

| Family size | 0.056 | 0.021 | 2.673 |

| Distance between household and forest | -0.137* | 0.081 | -1.680 |

| Regression constant | 7.600** | 0.125 | 60.710 |

| Multiple r | 0.352 | - | - |

| R2 | 0.124 | - | - |

| [1] |

Adhikari, B., di Falco, S., Lovett, J.C., 2004. Household characteristics and forest dependency: evidence from common property forest management in Nepal. Ecol. Econ. 48(2), 245-257.

doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2003.08.008 |

| [2] |

Adhikari, B., 2005. Poverty, property rights and collective action: understanding the distributive aspects of common property resource management. Environ. Dev. Econ. 10(1), 7-31.

doi: 10.1017/S1355770X04001755 |

| [3] |

Allendorf, T.D., 2006. Residents’ attitudes toward three protected areas in southwestern Nepal. Biodivers. Conserv. 16(7), 2087-2102.

doi: 10.1007/s10531-006-9092-z |

| [4] | Allendorf, T.D., Swe, K.K., Aung, M., et al., 2018. Community use and perceptions of a biodiversity corridor in Myanmar’s threatened southern forests. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 15, e00409. |

| [5] | Angelsen, A., Jagger, P., Babigumira, R., et al., 2014. Environmental income and rural livelihoods: a global-comparative analysis. World Dev. 64(Suppl.), 12-28. |

| [6] |

Appiah, M., Blay, D., Damnyag, L., et al., 2009. Dependence on forest resources and tropical deforestation in Ghana. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 11(3), 471-487.

doi: 10.1007/s10668-007-9125-0 |

| [7] | Arnold, J.E.M., Pérez, M.R., 2001. Can non-timber forest products match tropical forest conservation and development objectives? Ecol. Econ. 39(3), 437-447. |

| [8] |

Aung, P.S., Adam, Y.O., Pretzsch, J., et al., 2015. Distribution of forest income among rural households: a case study from Natma Taung national park, Myanmar. Forest, Trees and Livelihoods. 24(3), 190-201.

doi: 10.1080/14728028.2014.976597 |

| [9] |

Bebber, D.P., Butt, N., 2017. Tropical protected areas reduced deforestation carbon emissions by one third from 2000-2012. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 14005.

doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14467-w |

| [10] |

Belcher, B., Schreckenberg, K., 2007. Commercialisation of non-timber forest products: a reality check. Dev. Policy Rev. 25(3), 355-377.

doi: 10.1111/dpr.2007.25.issue-3 |

| [11] |

Boissière, M., Bastide, F., Basuki, I., et al., 2014. Can we make participatory NTFP monitoring work? Lessons learnt from the development of a multi-stakeholder system in Northern Laos. Biodivers. Conserv. 23(1), 149-170.

doi: 10.1007/s10531-013-0589-y |

| [12] |

Cavendish, W., 2000. Empirical regularities in the poverty-environment relationship of rural households: evidence from Zimbabwe. World Dev. 28(11), 1979-2003.

doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00066-8 |

| [13] |

Chou, P., 2018. The role of non-timber forest products in creating incentives for forest conservation: a case study of Phnom Prich Wildlife Sanctuary, Cambodia. Resources. 7(3), 41.

doi: 10.3390/resources7030041 |

| [14] |

Chowdhury, M.S.H., Koike, M., 2010. An overview on the protected area system for forest conservation in Bangladesh. J. For. Res. 21(1), 111-118.

doi: 10.1007/s11676-010-0019-x |

| [15] | CIFOR (Center for International Forestry Research), 2011. Forests and Non-Timber Forest Products. CIFOR Fact Sheets. [2021-05-26].http://www.cifor.cgiar.org/publications/corporate/factSheet/NTFP.htm. |

| [16] | Cocksedge, W., 2001. The role of co-operatives in the non-timber forest productindustry: Exploring issues and options using the case study of Salal (Gaultheria Shallon, Ericaceae). MSc Thesis. Victoria: University of Victoria. |

| [17] | CREL (Climate-Resilient Ecosystems and Livelihoods Project), 2015. Forest Carbon Inventory 2014: Eight Protected Areas in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Forest Department and Winrock International, Dhaka, Bangladesh. [2021-05-12].http://103.48.18.141/library/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Forest-Carbon-Inventory-2014-8-PAs.pdf. |

| [18] |

Cunningham, A.B., Ingram, W., Kadati, W., et al., 2017. Opportunities, barriers and support needs: micro-enterprise and small enterprise development based on non-timber products in eastern Indonesia. Australian Forestry. 80(3), 161-177.

doi: 10.1080/00049158.2017.1329614 |

| [19] |

Das, B.K., 2005. Role of NTFPs among forest villagers in a protected area of West Bengal. Journal of Human Ecology. 18(2), 129-136.

doi: 10.1080/09709274.2005.11905820 |

| [20] | Dash, M., Behera, B., 2013. Biodiversity conservation and local livelihoods: a study on Similipal Biosphere Reserve in India. Journal of Rural Development. 32(4), 409-426. |

| [21] |

Dash, M., Behera, B., Rahut, D.B., 2016. Determinants of household collection of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) and alternative livelihood activities in Similipal Tiger Reserve, India. Forest Policy Econ. 73, 215-228.

doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2016.09.012 |

| [22] | de Sousa, F.F., Vieira-da-Silva, C., Barros, F.B., 2018. The (in) visible market of miriti (Mauritia flexuosa L.f.) fruits, the “winter acai”, in Amazonian riverine communities of Abaetetuba, Northern Brazil. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 14, e00393. |

| [23] |

Dinda, S., Ghosh, S., Chatterjee, N.D., 2020. Understanding the commercialization patterns of non-timber forest products and their contribution to the enhancement of tribal livelihoods: an empirical study from Paschim Medinipur District, India. Small-scale For. 19(3), 371-397.

doi: 10.1007/s11842-020-09444-7 |

| [24] | Endamana, D., Angu, K.A., Akwah, G.N., et al., 2016. Contribution of non-timber forest products to cash and non-cash income of remote forest communities in Central Africa. Int. For. Rev. 18(3), 280-295. |

| [25] |

Epanda, M.A., Mukam Fotsing, A.J., Bacha, T., et al., 2019. Linking local people’s perception of wildlife and conservation to livelihood and poaching alleviation: a case study of the Dja biosphere reserve, Cameroon. Acta Oecol. Int. J. Ecol. 97, 42-48.

doi: 10.1016/j.actao.2019.04.006 |

| [26] |

Escobal, J., Aldana, U., 2003. Are nontimber forest products the antidote to rainforest degradation? Brazil nut extraction in Madre De Dios, Peru. World Dev. 31(11), 1873-1887.

doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2003.08.001 |

| [27] | Fardusi, M.J., Rahman, M.H., Roy, B., 2011. Improving livelihood status through collection and management of forest resources: an experience from Sylhet Forest Division, Bangladesh. International Journal of Forest Usufructs Management. 12(2), 59-76. |

| [28] | Garekae, H., Thakadu, O.T., Lepetu, J., 2016. Attitudes of local communities towards forest conservation in Botswana: a case study of Chobe Forest Reserve. Int. For. Rev. 18(2), 180-191. |

| [29] |

Geldmann, J., Coad, L., Barnes, M., et al., 2015. Changes in protected area management effectiveness over time: a global analysis. Biol. Conserv. 191, 692-699.

doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.08.029 |

| [30] | Gubbi, S., MacMillan, D.C., 2008. Can non-timber forest products solve livelihood problems? A case study from Periyar Tiger Reserve, India. Oryx. 42(2), 222-228. |

| [31] |

Hegde, R., Enters, T., 2000. Forest products and household economy: a case study from Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary, Southern India. Environ. Conserv. 27(3), 250-259.

doi: 10.1017/S037689290000028X |

| [32] |

Heino, M., Kummu, M., Makkonen, M., et al., 2015. Forest loss in protected areas and intact forest landscapes: a global analysis. PLoS ONE. 10(10), e0138918.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138918 |

| [33] |

Heltberg, R., Arndt, T.C., Sekhar, N.U., 2000. Fuelwood consumption and forest degradation: a household model for domestic energy substitution in rural India. Land Econ. 76(2), 213-232.

doi: 10.2307/3147225 |

| [34] |

Hernández-Barrios, J.C., Anten, N.P.R., Martínez-Ramos, M., 2015. Sustainable harvesting of non-timber forest products based on ecological and economic criteria. J. Appl. Ecol. 52(2), 389-401.

doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12384 |

| [35] |

Heubach, K., Wittig, R., Nuppenau, E.A., et al., 2011. The economic importance of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) for livelihood maintenance of rural west African communities: a case study from northern Benin. Ecol. Econ. 70(11), 1991-2001.

doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.05.015 |

| [36] | IPAC (Integrated Protected Area Co-management), 2009. Site-level Field Appraisal for Integrated Protected Area Co-Management: Khadimnagar National Park. Dhaka, Bangladesh. [2021-05-12].http://bfis.bforest.gov.bd/library/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/4-1-3-2-IPAC_Repor_PRA_Medhakachapia_NP.pdf. |

| [37] |

Kar, S.P., Jacobson, M.G., 2012. NTFP income contribution to household economy and related socio-economic factors: lessons from Bangladesh. Forest Policy Econ. 14(1), 136-142.

doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2011.08.003 |

| [38] |

Karanth, K.K., Nepal, S.K., 2012. Local residents perception of benefits and losses from protected areas in India and Nepal. Environ. Manage. 49(2), 372-386.

doi: 10.1007/s00267-011-9778-1 pmid: 22080427 |

| [39] |

Khan, M.A.S.A., Sultana, F., Rahman, M.H., et al., 2011. Status and ethno-medicinal usage of invasive plants in traditional health care practices: a case study from northeastern Bangladesh. J. For. Res. 22(4), 649-658.

doi: 10.1007/s11676-011-0174-8 |

| [40] |

Kim, S., Sasaki, N., Koike, M., 2008. Assessment of non-timber forest products in Phnom Kok community forest, Cambodia. Asia Eur. J. 6(2), 345-354.

doi: 10.1007/s10308-008-0180-4 |

| [41] |

Laurance, W.F., Carolina, U.D., Julio, R., et al., 2012. Averting biodiversity collapse in tropical forest protected areas. Nature. 489(7415), 290-294.

doi: 10.1038/nature11318 |

| [42] | Lepcha, L.D., Vineeta, V., Shukla, G., et al., 2020. Livelihood dependency on NTFP’s among forest dependent communities: an overview. Indian Forester. 146(7), 603-612. |

| [43] |

Mahonya, S., Shackleton, C.M., Schreckenberg, K., 2019. Non-timber forest product use and market chains along a deforestation gradient in southwest Malawi. Front. For. Glob. Change. 2, 71.

doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2019.00071 |

| [44] | Maiorano, L., Falcucci, A., Boitani, L., 2008. Size-dependent resistance of protected areas to land-use change. Proc. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 275(1640), 1297-1304. |

| [45] |

Mamo, G., Sjaastad, E., Vedeld, P., 2007. Economic dependence on forest resources: a case from Dendi District, Ethiopia. Forest Policy Econ. 9(8), 916-927.

doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2006.08.001 |

| [46] |

Matias, D.M.S., Tambo, J.A., Stellmacher, T., et al., 2018. Commercializing traditional non-timber forest products: an integrated value chain analysis of honey from giant honey bees in Palawan, Philippines. Forest Policy Econ. 97, 223-231.

doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2018.10.009 |

| [47] |

McElwee, P.D., 2008. Forest environmental income in Vietnam: household socioeconomic factors influencing forest use. Environ. Conserv. 35(2), 147-159.

doi: 10.1017/S0376892908004736 |

| [48] |

Mugido, W., Shackleton, C.M., 2019. The contribution of NTFPS to rural livelihoods in different agro-ecological zones of South Africa. Forest Policy Econ. 109, 101983.

doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2019.101983 |

| [49] |

Mujawamariya, G., Karimov, A.A., 2014. Importance of socio-economic factors in the collection of NTFPs: the case of gum arabic in Kenya. Forest Policy Econ. 42, 24-29.

doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2014.02.005 |

| [50] |

Mukul, S.A., Uddin, M.B., Manzoor Rashid, A.Z.M., et al., 2010. Integrating livelihoods and conservation in protected areas: understanding the role and stakeholder views on prospects for non-timber forest products, a Bangladesh case study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 17(2), 180-188.

doi: 10.1080/13504500903549676 |

| [51] |

Mushi, H., Yanda, P.Z., Kleyer, M., 2020. Socioeconomic factors determining extraction of non-timber forest products on the slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Hum. Ecol. 48(6), 695-707.

doi: 10.1007/s10745-020-00187-9 |

| [52] |

Nastran, M., 2015. Why does nobody ask us? Impacts on local perception of a protected area in designation, Slovenia. Land Use Pol. 46, 38-49.

doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.02.001 |

| [53] |

Ndumbe, L.N., Ingram, V., Tchamba, M., et al., 2019. From trees to money: the contribution of njansang (Ricinodendron huedelotii) products to value chain stakeholders’ financial assets in the South West Region of Cameroon. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods. 28(1), 52-67.

doi: 10.1080/14728028.2018.1559107 |

| [54] |

Nerfa, L., Rhemtulla, J.M., Zerriffi, H., 2020. Forest dependence is more than forest income: development of a new index of forest product collection and livelihood resources. World Dev. 125, 104689.

doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104689 |

| [55] |

Ojea, E., Loureiro, M.L., Alló, M., et al., 2015. Ecosystem services and REDD: estimating the benefits of non-carbon services in worldwide forests. World Dev. 78, 246-261.

doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.002 |

| [56] | Oldekop, J.A., Holmes, G., Harris, W.E., et al., 2015. A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conserv. Biol. 30(1), 133-141. |

| [57] |

Paumgarten, F., Shackleton, C.M., 2011. The role of non-timber forest products in household coping strategies in South Africa: the influence of household wealth and gender. Popul. Env. 33(1), 108-131.

doi: 10.1007/s11111-011-0137-1 |

| [58] |

Pengelly, R.D., Davidson-Hunt, I., 2012. Partnerships towards NTFP development: perspectives from Pikangikum First Nation. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy. 6(3), 230-250.

doi: 10.1108/17506201211258405 |

| [59] |

Prado Córdova, J.P., Wunder, S., Smith-Hall, C., et al., 2013. Rural income and forest reliance in highland Guatemala. Environ. Manage. 51, 1034-1043.

doi: 10.1007/s00267-013-0028-6 pmid: 23508886 |

| [60] | R Core, Team, 2019. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. [2021-05-18]. https://www.R-project.org/. |

| [61] | Rahman, M.H., Fardusi, M.J., Reza, M.S., 2011a. Traditional knowledge and use of medicinal plants by the Patra tribe community in the north-eastern region of Bangladesh. Proc. Pakistan Acad. Sci. 48(3), 159-167. |

| [62] | Rahman, M.H., Khan, M.A.S.A., Fardusi, M.J., et al., 2011b. Forest resources consumption by the Patra tribe community living in and around the Khadimnagar National Park, Bangladesh. International Journal of Forest Usufructs Management. 12(1), 95-111. |

| [63] |

Rahman, M.H., Fardusi, M.J., Roy, B., et al., 2012. Production, economics, employment generation and marketing pattern of rattan-based cottage enterprises: a case study from an urban area of north-eastern Bangladesh. Small-Scale For. 11, 207-221.

doi: 10.1007/s11842-011-9179-6 |

| [64] | Rahman, M.H., 2013. Attitude and perception of local communities towards sustainable co-management: a study from Rema-Kalenga Wildlife Sanctuary. In: Mustafa, M.G., Khan, N.A., Akhtaruzzaman, A.F.M., et al. (eds.). Co-Managed and Climate Resilient Ecosystems: Integrated Protected Area Co-Management in Bangladesh. Dhaka: USAID (United States Agency for International Development) and WorldFish, 67-94. |

| [65] |

Rahman, M.H., Alam, K., 2016. Forest dependent indigenous communities’ perception and adaptation to climate change through local knowledge in the protected area—a Bangladesh case study. Climate. 4(1), 12.

doi: 10.3390/cli4010012 |

| [66] |

Rahman, M.M., Mahmud, M.A.A., Ahmed, F.U., et al., 2017. Developing alternative income generation activities reduces forest dependency of the poor and enhances their livelihoods: the case of the Chunati Wildlife Sanctuary, Bangladesh. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods. 26(4), 256-270.

doi: 10.1080/14728028.2017.1320590 |

| [67] |

Rahman, M.H., Miah, M.D., 2017. Are protected forests of Bangladesh prepared to implementation of REDD+? A forest governance from Rema-Kalenga Wildlife Sanctuary. Environments. 4(2), 43.

doi: 10.3390/environments4020043 |

| [68] |

Rahman, M.H., Kitajima, K., Rahman, M.F., 2021. Spatial patterns of woodfuel consumption by commercial cooking sectors within 30 km of Lawachara National Park in northeastern Bangladesh. Energy Sustain Dev. 61, 118-128.

doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2021.01.008 |

| [69] |

Rana, M.P., Mukul, S.A., Sohel, M.S.I., et al., 2010. Economics and employment generation of bamboo-based enterprises: a case study from eastern Bangladesh. Small-Scale For. 9(1), 41-51.

doi: 10.1007/s11842-009-9100-8 |

| [70] |

Schneider, A., Hommel, G., Blettner, M., 2010. Linear regression analysis: part 14 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 107(44), 776-782.

doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0776 pmid: 21116397 |

| [71] | Shackleton, C., Shackleton, S., 2004. The importance of non-timber forest products in rural livelihood security and as safety nets: a review of evidence from South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 100, 658-664. |

| [72] |

Shackleton, C.M., Shackleton, S.E., 2006. Household wealth status and natural resource use in the Kat River Valley, South Africa. Ecol. Econ. 57(2), 306-317.

doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.04.011 |

| [73] | Shackleton, S., Shackleton, C., Shanley, P., 2011. Non-Timber Forest Products in the Global Context. Heidelberg: Springer. |

| [74] |

Soe, K.T., Yeo-Chang, Y., 2019. Perceptions of forest-dependent communities toward participation in forest conservation: a case study in Bago Yoma, South-Central Myanmar. Forest Policy Econ. 100, 129-141.

doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2018.11.009 |

| [75] |

Solomon, M.M., 2016. Importance of non-timber forest production in sustainable forest management, and its implication on carbon storage and biodiversity conservation in Ethiopia. International Journal of Biodiversity and Conservation. 8(11), 269-277.

doi: 10.5897/IJBC |

| [76] | Stanley, D., Voeks, R., Short, L., 2012. Is non-timber forest product harvest sustainable in the less developed world? A systematic review of the recent economic and ecological literature. Ethnobiol. Conserv. 1(9), 1-39. |

| [77] |

Steele, M.Z., Shackleton, C.M., Shaanker, R.U., et al., 2015. The influence of livelihood dependency, local ecological knowledge and market proximity on the ecological impacts of harvesting non-timber forest products. Forest Policy Econ. 50, 285-291.

doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2014.07.011 |

| [78] |

Suleiman, M.S., Wasonga, V.O., Mbau, J.S., et al., 2017. Non-timber forest products and their contribution to households income around Falgore Game Reserve in Kano, Nigeria. Ecol. Process. 6, 23.

doi: 10.1186/s13717-017-0090-8 |

| [79] | Sunderland, T., Achdiawan, R., Angelsen, A., et al., 2014. Challenging perceptions about men, women, and forest product use: a global comparative study. World Dev. 64(Suppl.1), 56-66. |

| [80] | Sunderland, T.C.H., Ndoye, O., Harrison-Sanchez, S., 2011. Non-timber forest products and conservation: what prospects? In: Shackleton, S., Shackleton, C., Shanley, P. (eds.). Non-Timber Forest Products in the Global Context. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, 209-224. |

| [81] |

Uddin, M.S., Mukul, S.A., Khan, M.A.S.A., et al., 2008. Small-scale agar (Aquilaria agallocha Roxb.) based cottage enterprises in Maulvibazar District of Bangladesh: production, marketing and potential contribution to rural development. Small-Scale For. 7, 139-149.

doi: 10.1007/s11842-008-9046-2 |

| [82] | UNEP-WCMC (United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre), IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), 2016. Protected Planet Report 2016: How Protected Area Contribute to Achieving Global Targets for Biodiversity. In: UNEP World Conservation Congress. Hawaii, USA. |

| [83] |

Vodouhê, F.G., Coulibaly, O., Adégbidi, A., et al., 2010. Community perception of biodiversity conservation within protected areas in Benin. Forest Policy Econ. 12(7), 505-512.

doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2010.06.008 |

| [84] | Vuola, M., Pyhälä, A., 2016. Local community perceptions of conservation policy: rights, recognition and reactions. Madagascar Conservation & Development. 11(2), 77-86. |

| [85] |

Youn, Y.C., 2009. Use of forest resources, traditional forest-related knowledge and livelihood of forest dependent communities: cases in South Korea. For. Ecol. Manage. 257(10), 2027-2034.

doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2009.01.054 |

| [86] | Zashimuddin, M., 2004. Community forestry for poverty reduction in Bangladesh. In: Sim, H.C., Appanah, S., Lu, W.M. (eds.). Proceeding of the Workshop Forests for Poverty Reduction: Can Community Forestry Make Money? Bangkok: FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, 81-94. |

| [1] | Soumen BISUI, Pravat Kumar SHIT. Assessing the role of forest resources in improving rural livelihoods in West Bengal of India [J]. Regional Sustainability, 2024, 5(2): 100141-. |

| [2] | Wakshum Shiferaw, Sebsebe Demissew, Tamrat Bekele, Ermias Aynekulu. Relationship between Prosopis juliflora invasion and livelihood diversification in the South Afar region, Northeast Ethiopia [J]. Regional Sustainability, 2020, 1(1): 82-92. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||

REGSUS Wechat

REGSUS Wechat

新公网安备 65010402001202号

新公网安备 65010402001202号