Regional Sustainability ›› 2024, Vol. 5 ›› Issue (2): 100141.doi: 10.1016/j.regsus.2024.100141cstr: 32279.14.j.regsus.2024.100141

• Full Length Article • Previous Articles Next Articles

Soumen BISUIa, Pravat Kumar SHITa,b,*( )

)

Received:2023-06-20

Revised:2024-03-08

Accepted:2024-06-11

Published:2024-06-30

Online:2024-07-25

Contact:

Pravat Kumar SHIT

E-mail:pravatgeo2007@gmail.com

Soumen BISUI, Pravat Kumar SHIT. Assessing the role of forest resources in improving rural livelihoods in West Bengal of India[J]. Regional Sustainability, 2024, 5(2): 100141.

Table 1

Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of households in inner, fringe, and outer villages."

| Variable | Percentage of households (%) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner villages | Fringe villages | Outer villages | |||

| Education | Less educated | 37.5 | 40.0 | 7.5 | 0.000 |

| Moderately educated | 61.7 | 54.2 | 71.7 | ||

| Highly educated | 0.8 | 5.8 | 20.8 | ||

| Gender | Male | 67.5 | 60.0 | 56.7 | 0.212 |

| Female | 32.5 | 40.0 | 43.3 | ||

| Cast | General | 4.2 | 7.5 | 5.0 | 0.408 |

| Scheduled cast | 5.0 | 5.8 | 6.7 | ||

| Scheduled tribe | 40.0 | 41.7 | 36.7 | ||

| Other | 50.8 | 45.0 | 51.7 | ||

| Household size | Small | 3.3 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 0.151 |

| Medium | 67.5 | 68.3 | 58.3 | ||

| Large | 29.2 | 28.3 | 39.2 | ||

| Standard of living | Low | 19.2 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.000 |

| Medium | 75.0 | 97.5 | 80.8 | ||

| High | 5.8 | 0.0 | 19.2 | ||

Table 3

Income of households in inner, fringe, and outer villages."

| Income source | Income in inner villages (INR) | Income in fringe villages (INR) | Income in outer villages (INR) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | |

| Timber | 5000.0 | 24,000.0 | 13,800.0 | 4000.0 | 15,000.0 | 8441.7 | 0.0 | 8000.0 | 2658.3 |

| Fuelwood | 5400.0 | 48,600.0 | 26,748.0 | 5400.0 | 32,400.0 | 16,565.0 | 1000.0 | 20,000.0 | 9458.3 |

| Medicine plant | 300.0 | 1500.0 | 1028.3 | 0.0 | 800.0 | 298.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Sal leaves | 8734.6 | 2000.0 | 15,300.0 | 2000.0 | 14,400.0 | 5819.2 | 0.0 | 4000.0 | 372.5 |

| Sal seed | 150.0 | 3000.0 | 1270.8 | 0.0 | 3000.0 | 680.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Honey | 0.0 | 700.0 | 245.0 | 0.0 | 500.0 | 204.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Kendu | 800.0 | 6000.0 | 3066.7 | 0.0 | 2000.0 | 283.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Mahua | 0.0 | 1100.0 | 629.3 | 0.0 | 500.0 | 171.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Mahua seed | 0.0 | 2100.0 | 630.8 | 0.0 | 500.0 | 267.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Forest income | 22,900.0 | 87,450.0 | 56,153.5 | 17,450.0 | 54,200.0 | 32,722.5 | 2400.0 | 27,000.0 | 12,492.5 |

| Agriculture income | 5000.0 | 22,000.0 | 13,193.8 | 5000.0 | 50,000.0 | 17,041.7 | 12,000.0 | 45,000.0 | 22,933.3 |

| Total income | 38,900.0 | 100,850.0 | 70,914.8 | 28,800.0 | 104,400.0 | 53,828.3 | 33,400.0 | 90,000.0 | 53,100.8 |

Fig. 3.

Photos showing the livelihood activities of households. (a), collection of Mustard seed; (b), agricultural labor in a rice field; (c), Babui collection; (d), grazing cows; (e), grazing goats; (f), poultry farming; (g), indigenous households’ activities revolve around the collection of Mahul flowers; (h), non-timber forest products; (i), collection of dry firewood from the surrounding forests; (j), collection of Sal leaves; (k), rearing pig; (l), selling of the firewood."

Table 4

Results of multivariate analysis."

| Statistic | Sum of squares | Degree of freedom | Mean square | F | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest income | 114,581,903,280.0 | 2 | 57,290,951,640.0 | 618.1 | 0.000 |

| Agriculture income | 5,775,107,291.6 | 2 | 2,887,553,645.8 | 48.2 | 0.000 |

| Livestock income | 133,811,669,791.6 | 2 | 66,905,834,895.8 | 162.6 | 0.000 |

| SLI | 3782.1 | 2 | 1891.0 | 49.0 | 0.000 |

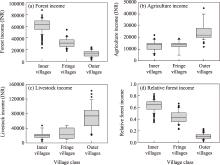

Fig. 4.

Variations in income sources and relative forest income in different village classes. (a), forest income; (b), agriculture income; (c), livestock income (d), relative forest income. The boxes represent the range from the lower quantile (Q25) to the upper quantile (Q75). The horizontal lines inside the boxes represent medians. The dots outside the boxes represent outliers. The upper and lower whiskers indicate the maximum and minimum values, respectively. Exchange rate: 83.5 INR=1.0 USD."

| [1] | Adhikary P.P., Shit P.K., Bhunia G.S., 2021. NTFPs for socioeconomic security of rural households along the forest ecotone of Paschim Medinipur forest division, India. Forest Resources Resilience and Conflicts. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-822931-6.00018-6. |

| [2] | Babulo B., Muys B., Nega F., 2009. The economic contribution of forest resource use to rural livelihoods in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. For. Policy Econ. 11(2), 109-117. |

| [3] | Basar S.M.A., Das P., 2018. Status of food security in West Bengal: A study based on NSSO unit level data. International Journal of Inclusive Development. 4(1), 1-7. |

| [4] | Belcher B.M., 2005. Forest product markets, forests and poverty reduction. International Forestry Review. 7(2), 82-89. |

| [5] | Belcher B., Achdiawan R., Dewi S., 2015. Forest-based livelihoods strategies conditioned by market remoteness and forest proximity in Jharkhand, India. World Dev. 66, 269-279. |

| [6] | Bisui S., Roy S., Sengupta D., et al., 2021a. Conversion of land use land cover and its impact on ecosystem services in a tropical forest. In: ShitP.K., PourghasemiH.R., DasP., et al., (eds.). Spatial Modeling in Forest Resources Management. Environmental Science and Engineering. Cham: Springer. |

| [7] | Bisui S., Roy S., Sengupta D., et al., 2021b. Assessment of ecosystem services values in response to land use/land cover change in tropical forest. Forest Resources Resilience and Conflicts. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-822931-6.00031-9. |

| [8] | Bisui S., Roy S., Bera B., et al., 2022. Economic and ecological realization of Joint Forest Management (JFM) for sustainable rural livelihood: A case study. Trop. Ecol. 64, 296-306. |

| [9] | Bisui S., Shit P.K., 2023. Assessing the dependence of livelihoods in rural communities on tropical forests: Insights from the Midnapore Forest Division in West Bengal, India. Socio Ecol. Pract. Res. 5, 423-437. |

| [10] | Cavendish W., 2000. Empirical regularities in the poverty-environment relationship of rural households: Evidence from Zimbabwe. World Dev. 28(11), 1979-2003. |

| [11] | Champion H.G., Seth S.K., 1968. A Revised Survey of the Forest Types of India. [2023-12-30]. https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=hIjwAAAAMAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR15&dq=Champion,+H.G.,+Seth,+S.K.,+1968.+A+Revised+Survey+of+the+Forest+Types+of+India.+XX:+Manag.+Publ.&ots=lEtV3Ho_y2&sig=VLMeVgOQvw3dNFuU-aAHwf5EcOA&redir_esc= y#v=onepage&q&f=false. |

| [12] | Chou T.C., 2019. Design for empowerment:Bolstering knowledge and skills to aid sustainable awareness and actions. PhD Dissertation. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University. |

| [13] | Cocks M., López C., Dold T., 2011. Cultural importance of non-timber forest products: Opportunities they pose for bio-cultural diversity in dynamic societies. [2023-12-30]. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-17983-9_5. |

| [14] | Das G.K., Das R., 2016. Mapping of the forest cover based on multi-criteria analysis: A case study on Jhargram sector in Paschim Medinipur District. Int. J. Sci. Res. 5(8), 492-499. |

| [15] | Dash M., Behera B., 2016. Determinants of household collection of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) and alternative livelihood activities in Similipal Tiger Reserve, India. For. Policy Econ. 73, 215-228. |

| [16] | Delgado T.S., McCall M.K., López-Binqüist C., 2016. Recognized but not supported: Assessing the incorporation of non-timber forest products into Mexican forest policy. For. Policy Econ. 71, 36-42. |

| [17] | de Sousa F.F., Vieira-da-Silva C., Barros F.B., 2018. The (in)visible market of miriti (Mauritia flexuosa L.f.) fruits, the “winter acai”, in Amazonian riverine communities of Abaetetuba, Northern Brazil. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 14, e00393, doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00393. |

| [18] |

Edwards P., Sharma‐Wallace L., Barnard T., et al., 2019. Sustainable livelihoods approaches to inform government‐local partnerships and decision‐making in vulnerable environments. New Zealand Geographer. 75(2), 63-73.

doi: 10.1111/nzg.12214 |

| [19] | Fardusi M.J., Rahman M.H., Roy B., 2011. Improving livelihood status through collection and management of forest resources: An experience from Sylhet Forest Division, Bangladesh. Int. J. For. Usufructs Manag. 12(2), 59-76. |

| [20] | Fardusi M.J., Chianucci F., Barbati A., 2017. Concept to practice of geospatial-information tools to assist forest management and planning under precision forestry framework: A review. Ann. Silvic. Res. 41(1), 3-14. |

| [21] | Garekae H., Thakadu O.T., Lepetu J., 2017. Socio-economic factors influencing household forest dependency in Chobe enclave, Botswana. Ecol. Processes. 6(1), 1-10. |

| [22] | IIPS(International Institute for Population Sciences), ORC Macro, 2000. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2), 1998-99: India. [2023-12-30]. https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FRIND2/FRIND2.pdf. |

| [23] | Jagger P., Luckert M.M.K., Duchelle A.E., et al., 2014. Tenure and forest income: Observations from a global study on forests and poverty. World Dev. 64, 43-55. |

| [24] | Jana S.K., Ahmed M.U., Heubach K., 2017. Dependency of rural households on non-timber forest products (NTFPs): A study in dryland areas of West Bengal, India. Int. J. Sustain. Econom. Manag. 6(2), 37-50. |

| [25] | Jana S.K., Payra T., Manna S.S., et al., 2019. Forest dependency and rural livelihood—a study in Paschim Medinipur District, West Bengal. Asian Journal of Multidimensional Research. 8(3), 164-178. |

| [26] | Kamanga P., Vedeld P., Sjaastad E., 2009. Forest incomes and rural livelihoods in Chiradzulu District, Malawi. Ecol. Econ. 68(3), 613-624. |

| [27] | Kar S.P., Jacobson M.G., 2012. NTFP income contribution to household economy and related socio-economic factors: Lessons from Bangladesh. For. Policy Econ. 14(1), 136-142. |

| [28] | Langat D.K., Maranga E.K., Aboud A.A., et al., 2016. Role of forest resources to local livelihoods: The case of East Mau forest ecosystem, Kenya. Int. J. For. Res. 2016, 4537354, doi: 10.1155/2016/4537354. |

| [29] | Lax J., Köthke M., 2017. Livelihood strategies and forest product utilisation of rural households in Nepal. Small-scale For. 16(4), 505-520. |

| [30] | Mahapatra A.K., Shackleton C.M., 2011. Has deregulation of non-timber forest product controls and marketing in Orissa state (India) affected local patterns of use and marketing. For. Policy Econ. 13(8), 622-629. |

| [31] | Mahonya S., Shackleton C.M., Schreckenberg K., 2019. Non-timber forest product use and market chains along a deforestation gradient in southwest Malawi. Front. For. Glob. Change. 2, doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2019.00071. |

| [32] | Makhubele L., Chirwa P.W., Araia M.G., 2022. The influence of forest proximity to harvesting and use of provisioning ecosystem services from tree species in traditional agroforestry landscapes. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 29(8), 812-826. |

| [33] | Matias D.M.S., Tambo J.A., Stellmacher T., et al., 2018. Commercializing traditional non-timber forest products: An integrated value chain analysis of honey from giant honey bees in Palawan, Philippines. For. Policy Econ. 97, 223-231. |

| [34] | Mendako R.K., Tian G., Ullah S., et al., 2022. Assessing the economic contribution of forest use to rural livelihoods in the Rubi-Tele Hunting Domain, DR Congo. Forests. 13(1), 130, doi: 10.3390/f13010130. |

| [35] | Mukherjee P., Ray B., Bhattacharya R.N., 2017. Status differences in collective action and forest benefits: Evidence from joint forest management in India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 19(5), 1831-1854. |

| [36] | Mukul S.A., Uddin M.B., Rashid A.Z.M., et al., 2010. Integrating livelihoods and conservation in protected areas: Understanding the role and stakeholder views on prospects for non-timber forest products, a Bangladesh case study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 17(2), 180-188. |

| [37] | Mukul S.A., Rashid A.M., Uddin M.B., et al., 2016. Role of non-timber forest products in sustaining forest-based livelihoods and rural households’ resilience capacity in and around protected area: A Bangladesh study. J. Environ. Plann. Manag. 59(4), 628-642. |

| [38] | Mushi H., Yanda P.Z., Kleyer M., 2020. Socioeconomic factors determining extraction of non-timber forest products on the slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Hum. Ecol. 48, 695-707. |

| [39] | Nambiar E.K.S., 2021. Strengthening Vietnam’s forestry sectors and rural development: Higher productivity, value, and access to fairer markets are needed to support small forest growers. Trees, Forests and People. 3, 100052, doi: 10.1016/j.tfp.2020.100052. |

| [40] | Ndumbe L.N., Ingram V., Tchamba M., et al., 2019. From trees to money: The contribution of Njansang (Ricinodendron heudelotii) products to value chain stakeholders’ financial assets in the South West Region of Cameroon. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods. 28(1), 52-67. |

| [41] | Nerfa L., Rhemtulla J.M., Zerriffi H., 2020. Forest dependence is more than forest income: Development of a new index of forest product collection and livelihood resources. World Dev. 125, 104689, doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104689. |

| [42] | Ofoegbu C., Chirwa P.W., Francis J., et al., 2017. Socio-economic factors influencing household dependence on forests and its implication for forest-based climate change interventions. South. For. J. For. Sci. 79(2), 109-116. |

| [43] | Pradhan P., Singh M., 2019. Role of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) in sustaining forest-based livelihoods: A case study of Ribdi village of West Sikkim, India. [2023-06-01]. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20193414773. |

| [44] | Rahut D.B., Behera B., Ali A., 2016. Do forest resources help increase rural household income and alleviate rural poverty? Empirical evidence from Bhutan. For. Trees Livelihoods. 25(3), 187-198. |

| [45] | Sahoo K.P., Roy A., Mandal M.H., et al., 2022. Appraisal of coexistence and interdependence of forest and tribes in Jhargram District of West Bengal, India using SWOT-AHP analysis. GeoJournal. 88, 1493-1513. |

| [46] | Saxena A., Guneralp B., Bailis R., et al., 2016. Evaluating the resilience of forest dependent communities in Central India by combining the sustainable livelihoods framework and the cross scale resilience analysis. Current Science. 110(7), 1195-1207. |

| [47] | Schmerbeck J., Kohli A., Seeland K., 2015. Ecosystem services and forest fires in India—Context and policy implications from a case study in Andhra Pradesh. For. Policy Econ. 50, 337-346. |

| [48] | Sharma D., Tiwari B.K., Chaturvedi S.S., et al., 2015. Status, utilization and economic valuation of non-timber forest products of Arunachal Pradesh, India. J. For. Environ. Sci. 31(1), 24-37. |

| [49] | Shit P.K., Pati C.K., 2012. Non-timber forest products for livelihood security of tribal communities: A case study in Paschim Medinipur district, West Bengal. J. Hum. Ecol. 40(2), 149-156. |

| [50] | Shit P.K., Pourghasemi H.R., Das P., et al., 2020. Spatial Modeling in Forest Resources Management. Switzerland: Springer. |

| [51] | Shit P.K., Pourghasemi H.R., Adhikary P.P., et al., 2021. Forest Resources Resilience and Conflicts. Amsterdam: Elsevier. |

| [52] | Singh R., Gehlot A., Akram S.V., et al., 2022. Forest 4.0: Digitalization of forest using the Internet of Things (IoT). J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 34(8), 5587-5601. |

| [53] | Sukhdev P., 2009. Costing the Earth. Nature. 462, 277, doi: 10.1038/462277a. |

| [54] | Suleiman M.S., Wasonga V.O., Mbau J.S., et al., 2017. Non-timber forest products and their contribution to households’ income around Falgore Game Reserve in Kano, Nigeria. Ecol. Processes. 6(1), 1-14. |

| [55] | Thorbecke E., Charumilind C., 2002. Economic inequality and its socioeconomic impact. World Dev. 30(9), 1477-1495. |

| [56] |

Vaughan A., 2020. World braces for economic impact. New Sci. 245(3272), 10, doi: 10.1016/S0262-4079(20)30477-2.

pmid: 32287811 |

| [57] | Vedeld P., Angelsen A., Bojö J., et al., 2007. Forest environmental incomes and the rural poor. For. Policy Econ. 9(7), 869-879. |

| [58] | Walle Y., Nayak D., 2022. Analyzing households’ dependency on non-timber forest products, poverty alleviation potential, and socioeconomic drivers: Evidence from Metema and Quara districts in the dry Forests of Amhara Region, Ethiopia. J. Sustain. For. 41(8), 678-705. |

| [59] |

Wunder S., Börner J., Shively G., et al., 2014. Safety nets, gap filling and forests: A global-comparative perspective. World Dev. 64, 29-42.

doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.03.005 |

| [60] | Zikargae M.H., Woldearegay A.G., Skjerdal T., 2022. Empowering rural society through non-formal environmental education: An empirical study of environment and forest development community projects in Ethiopia. Heliyon. 8(3), e09127, doi: 10.1016/j. heliyon.2022.e09127. |

| [1] | Debanjan BASAK, Indrajit Roy CHOWDHURY. Role of self-help groups on socioeconomic development and the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) among rural women in Cooch Behar District, India [J]. Regional Sustainability, 2024, 5(2): 100140-. |

| [2] | Ramya Kundayi RAVI, Priya BABY, Nidhin ELIAS, Jisa George THOMAS, Kathyayani Bidadi VEERABHADRAIAH, Bharat PAREEK. Preparedness, knowledge, and perception of nursing students about climate change and its impact on human health in India [J]. Regional Sustainability, 2024, 5(1): 100116-. |

| [3] | Aishwarya BASU, Jyotish Prakash BASU. Impact of forest governance and enforcement on deforestation and forest degradation at the district level: A study in West Bengal State, India [J]. Regional Sustainability, 2023, 4(4): 441-452. |

| [4] | Sunil SAHA, Debabrata SARKAR, Prolay MONDAL. Assessing and mapping soil erosion risk zone in Ratlam District, central India [J]. Regional Sustainability, 2022, 3(4): 373-390. |

| [5] | Giribabu DANDABATHULA, Sudhakar Reddy CHINTALA, Sonali GHOSH, Padmapriya BALAKRISHNAN, Chandra Shekhar JHA. Exploring the nexus between Indian forestry and the Sustainable Development Goals [J]. Regional Sustainability, 2021, 2(4): 308-323. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||

REGSUS Wechat

REGSUS Wechat

新公网安备 65010402001202号

新公网安备 65010402001202号