Regional Sustainability ›› 2022, Vol. 3 ›› Issue (4): 281-293.doi: 10.1016/j.regsus.2022.11.001cstr: 32279.14.j.regsus.2022.11.001

• Full Length Article • Next Articles

Mahir YAZARa,*( ), Lukas HERMWILLEb, Håvard HAARSTADa

), Lukas HERMWILLEb, Håvard HAARSTADa

Received:2022-05-30

Revised:2022-10-12

Accepted:2022-11-04

Published:2022-12-30

Online:2023-01-31

Contact:

Mahir YAZAR

E-mail:Mahir.Yazar@uib.no

Mahir YAZAR, Lukas HERMWILLE, Håvard HAARSTAD. Right-wing and populist support for climate mitigation policies: Evidence from Poland and its carbon-intensive Silesia region[J]. Regional Sustainability, 2022, 3(4): 281-293.

Table S1

Distribution properties of the 2016 European Social Survey (ESS) and the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) variables considered by this study."

| Variable | Category | Distribution description | Proportion of respondents against complete sample size for Poland (%) | Proportion of respondents against complete sample size for Silesia region (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Respondents’ extent of support for increasing taxes on fossil fuels | Strongly and somewhat in favour | 14.0 | 20.0 |

| Other than strongly and somewhat in favour (neither in favour nor against, somewhat against, and strongly against) | 86.0 | 80.0 | ||

| Respondents’ extent of support for using public money to subsidize renewable energy | Strongly and somewhat in favour | 76.0 | 79.0 | |

| Other than strongly and somewhat in favour (neither in favour nor against, somewhat against, and strongly against) | 24.0 | 21.0 | ||

| Socio-political factor | Respondents voted party-political ideology | Voted for extreme-right party | 14.0 | 12.0 |

| Voted for right-wing party | 45.0 | 33.0 | ||

| Voted for center party | 31.0 | 37.0 | ||

| Voted for left-wing party | 11.0 | 18.0 | ||

| Respondents voted party anti-elitist and anti-establishment rhetoric | Voted for party for which populist rhetoric is not important or closer to not important | 41.0 | 47.0 | |

| Moderately to extremely important | 59.0 | 53.0 | ||

| Respondents concerned about climate change | Extremely, very, and somewhat concerned | 65.0 | 74.0 | |

| Not at all and not very concerned | 35.0 | 26.0 | ||

| Socio-demographic factor | Respondent gender | Female | 51.0 | 58.0 |

| Male | 49.0 | 42.0 | ||

| Respondent age | ≤40 years old | 39.0 | 28.0 | |

| 41-55 years old | 24.0 | 45.0 | ||

| ≥56 years old | 37.0 | 27.0 | ||

| Respondent education level | College, graduate/professional school | 32.0 | 45.0 | |

| Grades of 1-11, high school, community, vocational, technical | 68.0 | 55.0 | ||

| Respondent employment status | Employed | 56.0 | 53.0 | |

| Unemployed | 44.0 | 47.0 | ||

| Respondent employment sector | Carbon intensive sector | 18.0 | 35.0 | |

| Other than carbon-intensive sector | 82.0 | 65.0 |

Table S2

Cramer’s V results of the strength of association between the independent and control variables."

| Variable pair | Cramer’s V | |

|---|---|---|

| Poland | Silesia region | |

| Voted party ideology (VPA) and populism | 0.1762510 | 0.1461240 |

| VPA and concern about climate change | 0.1298744 | 0.2910516 |

| VPA and gender | 0.1432053 | 0.2009083 |

| VPA and age | 0.2441867 | 0.2471347 |

| VPA and employment status | 0.1774700 | 0.2227578 |

| VPA and employment sector | 0.3181341 | 0.5422207 |

| VPA and education level | 0.1941230 | 0.2122858 |

| Populism and concern about climate change | 0.1328435 | 0.2963634 |

| Populism and gender | 0.1442447 | 0.2036453 |

| Populism and age | 0.2450344 | 0.2483338 |

| Populism and employment status | 0.1847627 | 0.2344642 |

| Populism and employment sector | 0.3117971 | 0.5283008 |

| Populism and education level | 0.1902861 | 0.2375252 |

| Concern about climate change and gender | 0.0774495 | 0.2481088 |

| Concern about climate change and age | 0.0776424 | 0.2110847 |

| Concern about climate change and employment status | 0.1161647 | 0.1868813 |

| Concern about climate change and employment sector | 0.2612512 | 0.5276983 |

| Concern about climate change and education level | 0.1759413 | 0.2809426 |

| Gender and age | 0.0555019 | 0.7173746 |

| Gender and employment status | 0.1355360 | 0.2613072 |

| Gender and employment sector | 0.2289976 | 0.2695296 |

| Gender and education level | 0.2463501 | 0.3511801 |

| Age and employment status | 0.1158719 | 0.1210854 |

| Age and employment sector | 0.3455976 | 0.4905879 |

| Age and education level | 0.2590689 | 0.2858667 |

| Employment status and employment sector | 0.3792286 | 0.6298269 |

| Employment status and education level | 0.3821664 | 0.4780276 |

| Employment sector and education level | 0.2670497 | 0.4709967 |

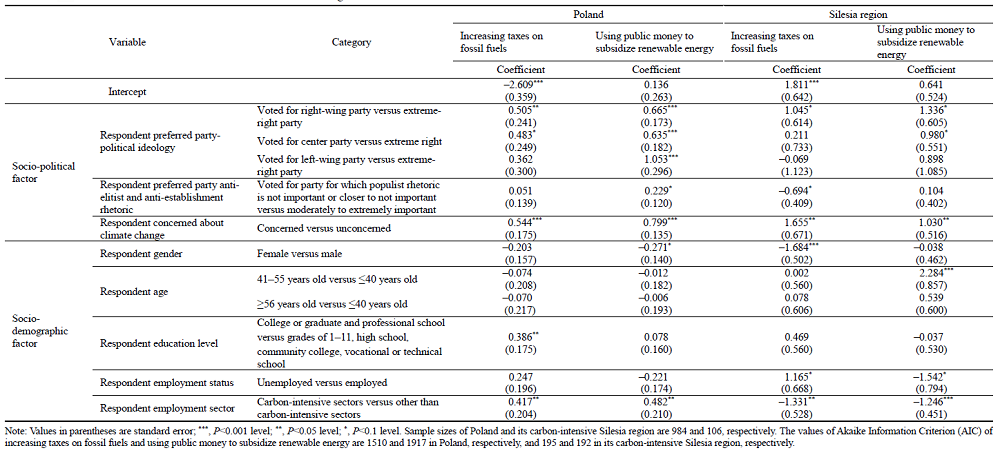

Table 1

Individual-level logistic regression models for the relationships between the two dependent variables (increasing taxes on fossil fuels and using public money to subsidize renewable energy) for socio-political and demographic factors in Poland and its carbon-intensive Silesia region."

|

Table 2

Statistically significant effects of the socio-political and demographic factors on the two climate mitigation policies."

| Variable | Category | Increasing taxes on fossil fuels | Using public money to subsidize renewable energy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poland | Silesia region | Poland | Silesia region | |||

| Socio-political factor | Respondent preferred party-political ideology | Voted for right-wing party versus extreme-right party | + | + | + | + |

| Voted for center party versus extreme-right party | + | + | + | |||

| Voted for left-wing party versus extreme-right party | + | |||||

| Respondent preferred party anti-elitist and anti-establishment rhetoric | Voted for party where populist rhetoric is not important to close to not important versus moderately to extremely important | - | + | |||

| Respondent concerned about climate change | Concerned versus unconcerned | + | + | + | + | |

| Socio-demographic factor | Respondent gender | Female versus male | - | - | ||

| Respondent age | 41-56 years old versus ≤40 years old | + | ||||

| Respondent education level | College or graduate and professional school versus grades of 1-11, high school, community college, and vocational or technical school | + | ||||

| Respondent employment status | Unemployed versus employed | + | - | |||

| Respondent employment sector | Carbon-intensive sector versus other than carbon-intensive sectors | + | - | + | - | |

| [1] |

Baigorrotegui, G., 2019. Destabilization of energy regimes and liminal transition through collective action in Chile. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 55, 198-207.

doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2019.05.018 |

| [2] | Bakker, R., Edwards, E., Hooghe, L., et al., 2015. 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey. North Carolina: University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, USA. |

| [3] |

Ballew, M.T., Goldberg, M.H., Rosenthal, S.A., et al., 2019. Climate change activism among Latino and White Americans. Front. Commun. 3(58), 1-15.

doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2018.00001 |

| [4] | Baranzini, A., van den Bergh, J., Carattini, S., et al., 2017. Carbon pricing in climate policy: Seven reasons, complementary instruments, and political economy considerations. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. 8(4), 1-17. |

| [5] |

Batel, S., Devine-Wright, P., 2018. Populism, identities and responses to energy infrastructures at different scales in the United Kingdom: A post-Brexit reflection. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 43, 41-47.

doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2018.05.011 |

| [6] |

Bergek, A., Berggren, C., Magnusson, T., et al., 2013. Technological discontinuities and the challenge for incumbent firms: Destruction, disruption or creative accumulation? Res. Policy. 42(6-7), 1210-1224.

doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2013.02.009 |

| [7] |

Berkhout, F., 2006. Normative expectations in systems innovation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 18(3-4), 299-311.

doi: 10.1080/09537320600777010 |

| [8] |

Binz, C., Coenen, L., Murphy, J.T., et al., 2020. Geographies of transition—From topical concerns to theoretical engagement: A comment on the transitions research agenda. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 34, 1-3.

doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2019.11.002 |

| [9] | Brulle, R.J., Carmichael, J., Jenkins, J.C., 2012. Shifting public opinion on climate change: An empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the US, 2002-2010. Clim. Change. 114(2), 169-188. |

| [10] | Bukowski, M., Śniegocki, A., Wetmańska, Z., 2018. From Restructuring to Sustainable Development: The Case of Upper Silesia. Warsaw: WiseEuropa. |

| [11] |

Caprotti, F., Essex, S., Phillips, J., et al., 2020. Scales of governance: Translating multiscalar transitional pathways in South Africa’s energy landscape. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 70, 101700, doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101700.

doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101700 |

| [12] |

Carattini, S., Kallbekken, S., Orlov, A., 2019. How to win public support for a global carbon tax. Nature. 565(7739), 289-291.

doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-00124-x |

| [13] |

Cullen, R., 2017. Evaluating renewable energy policies. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 61(1), 1-18.

doi: 10.1111/1467-8489.12175 |

| [14] |

Decker, F., Lewandowsky, M., 2017. Rechtspopulismus in Europa: Erscheinungsformen, ursachen und gegenstrategien. Zeitschrift für Politik. 64(1), 21-38.

doi: 10.5771/0044-3360-2017-1-21 |

| [15] | Dzieciolowski, K., Hacaga, M., 2015. Polish Coal at the Turning Point: Uneasy Past, Challenging Future. [2022-02-07]. http://ensec.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=588:polish-coal-at-the-turning-point-uneasy-past-challenging-future&catid=126:kr&Itemid=395. |

| [16] |

Eakin, H., York, A., Aggarwal, R., et al., 2016. Cognitive and institutional influences on farmers’ adaptive capacity: Insights into barriers and opportunities for transformative change in central Arizona. Reg. Environ. Change. 16, 801-814.

doi: 10.1007/s10113-015-0789-y |

| [17] | European Social Survey, 2016. Welfare attitudes: Question design final module in template. London: ESS ERIC Headquarters c/o City, University of London. |

| [18] | EuroStat, 2019. Energy Imports Dependency. [2022-03-12]. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/-/nrg_ind_id. |

| [19] |

Fairbrother, M., Sevä, I.J., Kulin, J., 2019. Political trust and the relationship between climate change beliefs and support for fossil fuel taxes: Evidence from a survey of 23 European countries. Globl. Environ. Chang. 59, 102003, doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.102003.

doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.102003 |

| [20] |

Farla, J.C.M., Markard, J., Raven, R., et al., 2012. Sustainability transitions in the making: A closer look at actors, strategies and resources. Technol. Forecast Soc. Chang. 79(6), 991-998.

doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2012.02.001 |

| [21] | Fisher, S.L., Smith, B.E., (eds.). 2012. Transforming Places:Lessons from Appalachia. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. |

| [22] |

Forchtner, B., 2019. Climate change and the far right. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change. 10(5), e604, doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.604.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.604 |

| [23] | Geels, F.W., Schot, J., 2010. The dynamics of transitions:A socio-technical perspective. In: JGrin., JRotmans., JSchot., (eds.). Transitions to Sustainable Development—New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change. New York: Routledge, 11-104. |

| [24] | Goldberg, A.C., Brosius, A., de Vreese, C.H., 2021. Policy responsibility in the multilevel EU structure—the (non-) effect of media reporting on citizens’ responsibility attribution across four policy areas. J. Eur. Integr. 1-29. |

| [25] | Goldberg, M.H., Gustafson, A., Ballew, M.T., et al., 2020. Identifying the most important predictors of support for climate policy in the United States. Behav. Public Policy. 1-23. |

| [26] |

Grothmann, T., Patt, A., 2005. Adaptive capacity and human cognition: The process of individual adaptation to climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 15, 199-213.

doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.01.002 |

| [27] |

Hamilton, L.C., Hartter, J., Saito, K., 2015. Trust in scientists on climate change and vaccines. Sage Open. 5(3), doi: 10.1177/2158244015602752.

doi: 10.1177/2158244015602752 |

| [28] |

Harich, J., 2010. Change resistance as the crux of the environmental sustainability problem. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 26(1), 35-72.

doi: 10.1002/sdr.431 |

| [29] | Henderson, J., Sen, A., 2021. The energy transition: Key challenges for incumbent and new players in the global energy system. Oxford: the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. |

| [30] | Hermwille, L., 2021. What Makes a Region? [2022-03-12]. https://coaltransitions.org/news/what-makes-a-region/. |

| [31] |

Herrfahrdt-Pähle, E., Schlüter, M., Olsson, P., et al., 2020. Sustainability transformations: Socio-political shocks as opportunities for governance transitions. Glob Environ Chang. 63, 102097, doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102097.

doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102097 |

| [32] |

Hess, D.J., Renner, M., 2019. Conservative political parties and energy transitions in Europe: Opposition to climate mitigation policies. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 104, 419-428.

doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2019.01.019 |

| [33] |

Hess, D.J., McKane, R.G., Belletto, K., 2021. Advocating a just transition in Appalachia: Civil society and industrial change in a carbon-intensive region. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 75, 102004, doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2021.102004.

doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2021.102004 |

| [34] |

Hornsey, M.J., Harris, E.A., Fielding, K.S., 2018. Relationships among conspiratorial beliefs, conservatism and climate scepticism across nations. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8(7), 614-620.

doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0157-2 |

| [35] | Huber, R.A., Maltby, T., Szulecki, K., et al., 2021. Is populism a challenge to European energy and climate policy? Empirical evidence across varieties of populism. J. Eur. Public Policy. 1-20. |

| [36] | Jahn, D., 2021. Quick and dirty: How populist parties in government affect greenhouse gas emissions in EU member states. J. Eur. Public Policy. 1-18. |

| [37] |

Jenkins-Smith, H.C., Ripberger, J.T., Silva, C.L., et al., 2020. Partisan asymmetry in temporal stability of climate change beliefs. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10(4), 322-328.

doi: 10.1038/s41558-020-0719-y |

| [38] |

Jensen, J.S., Fratini, C.F., Cashmore, M.A., 2016. Socio-technical systems as place-specific matters of concern: The role of urban governance in the transition of the wastewater system in Denmark. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 18(2), 234-252.

doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2015.1074062 |

| [39] |

Kivimaa, P., Kern, F., 2016. Creative destruction or mere niche support? Innovation policy mixes for sustainability transitions. Res. Policy. 45(1), 205-217.

doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2015.09.008 |

| [40] |

Klenert, D., Mattauch, L., Combet, E., et al., 2018. Making carbon pricing work for citizens. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8(8), 669-677.

doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0201-2 |

| [41] |

Kuchler, M., Bridge, G., 2018. Down the black hole: Sustaining national socio-technical imaginaries of coal in Poland. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 41, 136-147.

doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2018.04.014 |

| [42] |

Kulin, J., Johansson Sevä, I., 2019. The role of government in protecting the environment: Quality of government and the translation of normative views about government responsibility into spending preferences. Int. J. Sociol. 49(2), 110-129.

doi: 10.1080/00207659.2019.1582964 |

| [43] | Kulin, J., Johansson Sevä, I., Dunlap, R.E., 2021. Nationalist ideology, rightwing populism, and public views about climate change in Europe. Env. Polit. 1-24. |

| [44] |

Kuokkanen, A., Nurmi, A., Mikkilä, M., et al., 2018. Agency in regime destabilization through the selection environment: The Finnish food system’s sustainability transition. Res. Policy. 47(8), 1513-1522.

doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2018.05.006 |

| [45] |

Kuokkanen, A., Yazar, M., 2018. Cities in sustainability transitions: Comparing Helsinki and Istanbul. Sustainability. 10(5), 1421, doi: 10.3390/su10051421.

doi: 10.3390/su10051421 |

| [46] |

Leipprand, A., Flachsland, C., 2018. Regime destabilization in energy transitions: The German debate on the future of coal. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 40, 190-204.

doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2018.02.004 |

| [47] |

Leiserowitz, A., 2006. Climate change risk perception and policy preferences: The role of affect, imagery, and values. Clim. Change. 77(1), 45-72.

doi: 10.1007/s10584-006-9059-9 |

| [48] |

Lockwood, M., 2018. Right-wing populism and the climate change agenda: exploring the linkages. Env. Polit. 27(4), 712-732.

doi: 10.1080/09644016.2018.1458411 |

| [49] | Markard, J., Raven, R., Truffer, B., 2012. Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects, Res. Policy. 41(6), 955-967. |

| [50] |

McCright, A.M., 2011. Political orientation moderates Americans’ beliefs and concern about climate change. Clim. Change. 104(2), 243-253.

doi: 10.1007/s10584-010-9946-y |

| [51] |

McCright, A.M., Dunlap, R.E., Marquart-Pyatt, S.T., 2016. Political ideology and views about climate change in the European Union. Env. Polit. 25(2), 338-358.

doi: 10.1080/09644016.2015.1090371 |

| [52] |

Mildenberger, M., Marlon, J.R., Howe, P.D., et al., 2017. The spatial distribution of Republican and Democratic climate opinions at state and local scales. Clim. Change. 145(3), 539-548.

doi: 10.1007/s10584-017-2103-0 |

| [53] | Mudde, C., Kaltwasser, C.R., 2013. Populism. In: Freeden, M., Sargent, L.T., Stears M., (eds.). Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 493-512. |

| [54] | Priest, S., 2016. Communicating Climate Change: The Path Forward. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 43-63. |

| [55] | R Core Team, 2013. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 9-12. |

| [56] | Ritchie, H., Roser, M., 2019. Poland: Energy Country Profile. Poland: Energy Country Profile—Our World in Data. [2022-03-12]. https://ourworldindata.org/energy/country/poland. |

| [57] | Runge, A., Runge, J., Kantor-Pietraga, I., et al., 2020. Does urban shrinkage require urban policy? The case of a post-industrial region in Poland. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 7(1), 476-494. |

| [58] |

Seto, K.C., Davis, S.J., Mitchell, R.B., et al., 2016. Carbon lock-in: Types, causes, and policy implications. Annu. Rev. of Environ. Resour. 41, 425-452.

doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-085934 |

| [59] | Shwom, R., Bidwell, D., Dan, A., et al., 2010. Understanding US public support for domestic climate change policies. Glob. Environ. Chang. 20(3), 472-482. |

| [60] |

Sivonen, J., 2020. Predictors of fossil fuel taxation attitudes across post-communist and other Europe. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy. 40(11/12), 1337-1355.

doi: 10.1108/IJSSP-02-2020-0044 |

| [61] |

Skoczkowski, T., Bielecki, S., Kochański, M., et al., 2020. Climate-change induced uncertainties, risks and opportunities for the coal-based region of Silesia: Stakeholders’ perspectives. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 35, 460-481.

doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2019.06.001 |

| [62] |

Smith, M.D., La Pierre, K.J., Collins, S.L., et al., 2015. Global environmental change and the nature of aboveground net primary productivity responses: insights from long-term experiments. Oecologia. 177(4), 935-947.

doi: 10.1007/s00442-015-3230-9 pmid: 25663370 |

| [63] |

Sovacool, B.K., 2021. Who are the victims of low-carbon transitions? Towards a political ecology of climate change mitigation. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 73, 101916.

doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2021.101916 |

| [64] | Spence, A., Poortinga, W., Pidgeon, N., 2012. The psychological distance of climate change. Risk Anal: Int. J. 32(6), 957-972. |

| [65] |

Sterner, T., 2007. Fuel taxes: An important instrument for climate policy. Energy Policy. 35(6), 3194-3202.

doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2006.10.025 |

| [66] | Szpor, A., Ziłkowska, K., 2018. The Transformation of the Polish Coal Sector. International Institute for Sustainable Development. [2022-03-12]. https://www.iisd.org/sites/default/files/publications/transformation-polish-coal-sector.pdf. |

| [67] | Szulecki, K., Ancygier, A., 2015. The New Polish Government’s Energy Policy: Expect more State, less Market. Energy Post. [2022-03-12]. https://energypost.eu/new-polishgovernments-energy-policy-expect-state-less-market/. |

| [68] |

Thornton, T.F., Mangalagiu, D., Ma, Y., et al., 2020. Cultural models of and for urban sustainability: assessing beliefs about Green-Win. Clim. Change. 160(4), 521-537.

doi: 10.1007/s10584-019-02518-2 |

| [69] |

Truffer, B., Coenen, L., 2012. Environmental innovation and sustainability transitions in regional studies. Reg. Stud. 46(1), 1-21.

doi: 10.1080/00343404.2012.646164 |

| [70] |

Turnheim, B., Geels, F.W., 2012. Regime destabilisation as the flipside of energy transitions: Lessons from the history of the British coal industry (1913-1997). Energy Policy. 50, 35-49.

doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2012.04.060 |

| [71] |

van der Linden, S., 2014. On the relationship between personal experience, affect and risk perception: The case of climate change. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 44(5), 430-440.

pmid: 25678723 |

| [72] |

Vona, F., 2019. Job losses and political acceptability of climate policies: why the ‘job-killing’ argument is so persistent and how to overturn it. Clim. Policy. 19(4), 524-532.

doi: 10.1080/14693062.2018.1532871 |

| [73] |

Wang, G.R., 1986. A Cramer rule for minimum-norm (T) least-squares (S) solution of inconsistent linear equations. Linear Algebra Appl. 74, 213-218.

doi: 10.1016/0024-3795(86)90123-0 |

| [74] | Wappelhorst, S., Pniewska, I., 2020. Emerging Electric Passenger Car Markets in Europe: Can Poland Lead the Way. Working Paper. [2022-03-12]. https://theicct.org/publication/emerging-electric-passenger-car-markets-in-europe-can-poland-lead-the-way/. |

| [75] | Weber, E.U., Stern, P.C., 2011. Public understanding of climate change in the United States. Am. Psycholt. 66(4), 315-328. |

| [76] | Wehnert, T., Hermwille, L., Mersmann, F., et al., 2018. Phasing-out Coal, Reinventing European Regions: An Analysis of EU Structural Funding in four European Coal Regions; Final Report. [2022-03-12]. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bsz:wup4-opus-71673. |

| [77] |

Yazar, M., Hestad, D., Mangalagiu, D., et al., 2020. Enabling environments for regime destabilization towards sustainable urban transitions in megacities: comparing Shanghai and Istanbul. Clim. Change. 160, 727-752.

doi: 10.1007/s10584-020-02726-1 |

| [78] |

Yazar, M., York, A., Kyriakopoulos, G., 2021. Heat exposure and the climate change beliefs in a Desert City: The case of Phoenix metropolitan area. Urban Clim. 36, 100769, doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2020.100769.

doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2020.100769 |

| [79] |

Yazar, M., York, A., 2022. Disentangling justice as recognition through public support for local climate adaptation policies: Insights from the Southwest US. Urban Clim. 41, 101079, doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2021.101079.

doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2021.101079 |

| [80] |

Yazar, M., York, A., Larson, K.L., 2022. Adaptation, exposure, and politics: Local extreme heat and global climate change risk perceptions in the Phoenix metropolitan region, USA. Cities. 127, 103763, doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2022.103763.

doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2022.103763 |

| [81] |

Żuk, P., Szulecki, K., 2020. Unpacking the right-populist threat to climate action: Poland’s pro-governmental media on energy transition and climate change. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 66, 101485, doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101485.

doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101485 |

| [82] |

Żuk, P., Żuk, P., Pluciński, P., 2021. Coal basin in Upper Silesia and energy transition in Poland in the context of pandemic: The socio-political diversity of preferences in energy and environmental policy. Res. Policy. 71, 101987, doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.101987.

doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.101987 |

| No related articles found! |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||

REGSUS Wechat

REGSUS Wechat

新公网安备 65010402001202号

新公网安备 65010402001202号