Regional Sustainability ›› 2022, Vol. 3 ›› Issue (2): 95-109.doi: 10.1016/j.regsus.2022.04.002

• Full Length Article • Next Articles

Dave Paladin BUENAVISTAa,b,*( ), Eefke Maria MOLLEEb, Morag MCDONALDb

), Eefke Maria MOLLEEb, Morag MCDONALDb

Received:2021-08-26

Revised:2022-02-21

Accepted:2022-04-18

Published:2022-06-30

Online:2022-09-19

Contact:

*E-mail address: Dave Paladin BUENAVISTA, Eefke Maria MOLLEE, Morag MCDONALD. Any alternatives to rice? Ethnobotanical insights into the dietary use of edible plants by the Higaonon tribe in Bukidnon Province, the Philippines[J]. Regional Sustainability, 2022, 3(2): 95-109.

Table 1

Formulas used for calculating the ethnobotanical indices in this study."

| Ethnobotanical index | Formula/Explanation | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Use-report (UR) | Total reported uses of each plant species in all the use-categories by all respondents. | Prance et al. ( |

| Use-value (UV) | UV=(∑Ui)/n, where Ui is the number of uses (counted based on the ith FAO food use-category) mentioned by each respondent; and n equals the total number of respondents interviewed. The UV index determines the most widely used edible plant species (the highest UV) as well as the underutilized species (the lowest UV, approaching 0). The UV index, however, cannot determine whether the species is used singly or for multiple purposes. | Phillips and Gentry ( |

| Number of uses (NU) | The sum of all the use-categories for which a species is cited. | Prance et al. ( |

| Fidelity level (FL; %) | FL=(ip/iu)×100%, expressed as the ratio of the total number of respondents who independently suggest the use of a species for a specific use-category (ip) and the total number of respondents who mention the plants for any uses irrespective of the use-category (iu). | Friedman et al. ( |

Table 2

Personal and socio-economic information of the 100 respondents from the Higaonon tribe."

| Statistic | Number of respondents (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Village | ||

| Bati-aw | 22 | 22.00 |

| Gabunan | 14 | 14.00 |

| Bundaan | 16 | 16.00 |

| Kalipayan | 24 | 24.00 |

| Dumalaguing | 24 | 24.00 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 26 | 26.00 |

| Female | 74 | 74.00 |

| Education | ||

| No formal education | 16 | 16.00 |

| Primary level | 73 | 73.00 |

| Secondary level | 10 | 10.00 |

| Tertiary level | 1 | 1.00 |

| Occupation | ||

| Farmer | 79 | 79.00 |

| Government employee | 3 | 3.00 |

| Others | 18 | 18.00 |

| Estimated monthly income | ||

| <19.49 USD per month | 52 | 52.00 |

| 19.49-97.45 USD per month | 47 | 47.00 |

| 116.94-194.90 USD per month | 1 | 1.00 |

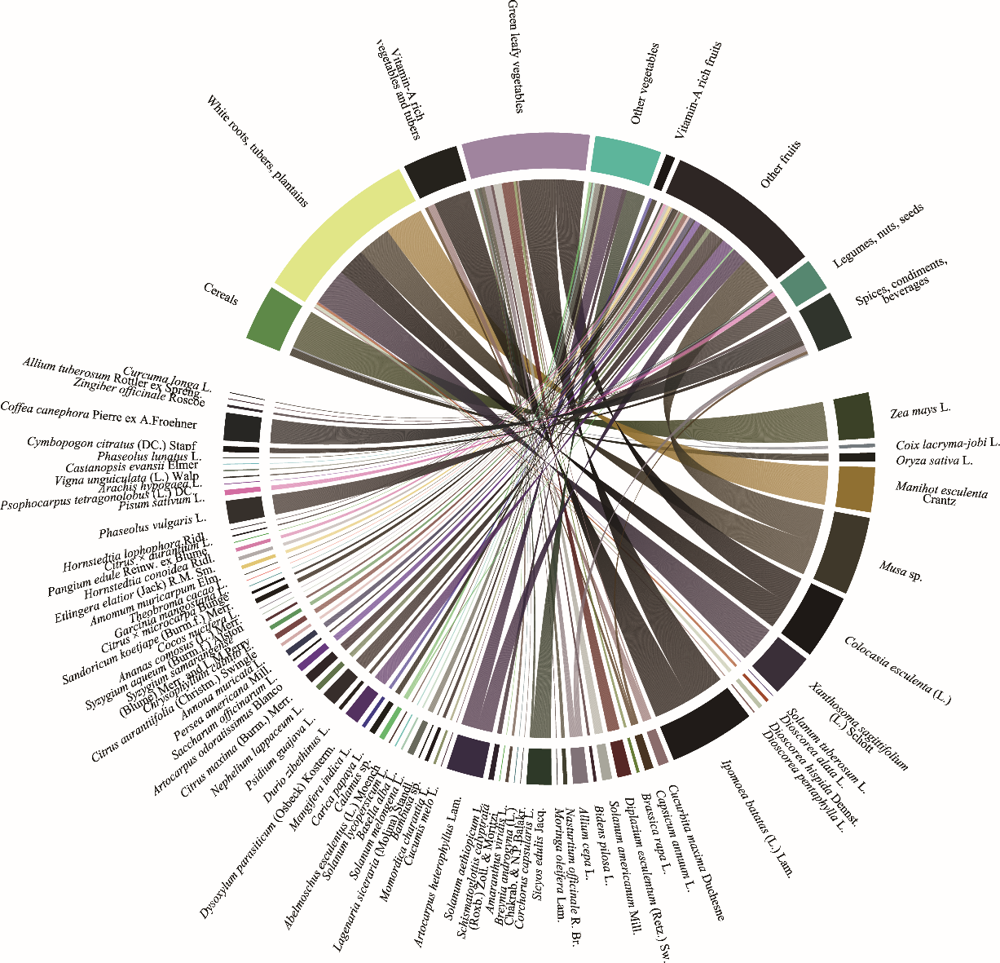

Fig. 3.

Chord diagram showing the distribution of 1254 use-reports (URs) for the 76 edible plant species (shown in the bottom half part of the chord diagram) utilized by the Higaonon tribe in the 9 use-categories (shown in the top half part of the chord diagram). The 9 use-categories include (1) cereals; (2) white roots, tubers, and plantains; (3) vitamin A-rich vegetables; (4) green leafy vegetables; (5) other vegetables; (6) vitamin-A rich fruits; (7) other fruits; (8) legumes, nuts, and seeds; and (9) spices, condiments, and beverages."

Table 3

Checklist of the 76 edible plant species utilized by the Higaonon tribe."

| Botanical family | Scientific name | Source | Life-form | Edible part | UR | UV | NU | FL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amaranthaceae | Amaranthus viridis L. | W | Herb | Leaf and shoot | 5 | 0.05 | 1 | G: 100% |

| Amaryllidaceae | Allium cepa L. | C | Herb | Leaf | 26 | 0.26 | 2 | G: 100%; S: 100% |

| Amaryllidaceae | Allium tuberosum Rottler ex Spreng. | C | Herb | Leaf | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | S: 100% |

| Anacardiaceae | Mangifera indica L. | C | Tree | Fruit | 6 | 0.06 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Annonaceae | Annona muricata L. | C | Tree | Fruit | 5 | 0.05 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Araceae | Xanthosoma sagittifolium (L.) Schott | C/W | Herb | Corm | 76 | 0.76 | 1 | W: 100% |

| Araceae | Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott | C/W | Herb | Corm and young leaf | 111 | 1.11 | 2 | W: 100%; G: 100% |

| Araceae | Schismatoglottis calyptrata (Roxb.) Zoll. & Moritzi | W | Herb | Young leaf | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | G: 100% |

| Arecaceae | Cocos nucifera L. | C | Tree | Fruit | 8 | 0.08 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Arecaceae | Calamus sp. | W | Shrub | Fruit and pith | 9 | 0.09 | 2 | OV: 100%; OF: 50% |

| Asteraceae | Bidens pilosa L. | W | Herb | Young leaf and shoot | 5 | 0.05 | 1 | G: 100% |

| Athyriaceae | Diplazium esculentum (Retz.) Sw. | W | Herb | Leaf and shoot | 24 | 0.24 | 1 | G: 100% |

| Bambusaceae | Bambusa sp. | W | Shrub | Shoot | 6 | 0.06 | 1 | OV: 100% |

| Basellaceae | Basella alba L. | C | Herb | Leaf and shoot | 3 | 0.03 | 1 | OV: 100% |

| Brassicaceae | Nasturtium officinale R. Br. | W | Herb | Leaf | 7 | 0.07 | 1 | G: 100% |

| Brassicaceae | Brassica rapa L. | C | Herb | Leaf and shoot | 5 | 0.05 | 1 | G: 100% |

| Bromeliaceae | Ananas comosus (L.) Merr. | C | Herb | Leaf | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Caricacaea | Carica papaya L. | C | Herb | Fruit | 10 | 0.10 | 1 | VF: 100% |

| Clusiaceae | Garcinia mangostana L. | C | Tree | Fruit | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Convolvulaceae | Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam. | C | Herb | Leaf, shoot, and tuber | 150 | 1.50 | 2 | VA: 100%; G: 100% |

| Cucurbitaceae | Sicyos edulis Jacq. | C | Herb | Leaf, shoot, and fruit | 43 | 0.43 | 2 | OV: 100%; G: 13.16% |

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucurbita maxima Duchesne | C | Herb | Shoot and fruit | 18 | 0.18 | 1 | VA: 100%; G: 20% |

| Cucurbitaceae | Momordica charantia L. | C | Herb | Shoot and fruit | 4 | 0.04 | 1 | OV: 100% |

| Cucurbitaceae | Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. | C | Herb | Fruit | 2 | 0.02 | 1 | OV: 100% |

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucumis melo L. | C | Herb | Fruit | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | OV: 100% |

| Dioscoreaceae | Dioscorea hispida Dennst. | W | Herb | Tuber | 7 | 0.07 | 1 | W: 100% |

| Dioscoreaceae | Dioscorea alata L. | C | Herb | Tuber | 5 | 0.05 | 1 | W: 100% |

| Dioscoreaceae | Dioscorea pentaphylla L. | W | Herb | Tuber | 2 | 0.02 | 1 | W: 100% |

| Euphorbiaceae | Manihot esculenta Crantz | C | Shrub | Tuber | 78 | 0.78 | 1 | W: 100% |

| Fabaceae | Phaseolus vulgaris L. | C | Herb | Pod and seed | 40 | 0.40 | 1 | L: 100% |

| Fabaceae | Pisum sativum L. | C | Herb | Pod and seed | 9 | 0.09 | 1 | L: 100% |

| Fabaceae | Arachis hypogaea L. | C | Herb | Seed | 2 | 0.02 | 1 | L: 100% |

| Fabaceae | Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp. | C | Herb | Pod and seed | 2 | 0.02 | 1 | L: 100% |

| Fabaceae | Phaseolus lunatus L. | C | Herb | Pod and seed | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | L: 100% |

| Fabaceae | Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC. | C | Herb | Pod and seed | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | L: 100% |

| Fagaceae | Castanopsis evansii Elmer | W | Tree | Seed | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | L: 100% |

| Lauraceae | Persea americana Mill. | C | Tree | Fruit | 10 | 0.10 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Malvaceae | Durio zibethinus L. | C | Tree | Fruit | 6 | 0.06 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Malvaceae | Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench | C | Herb | Fruit | 2 | 0.02 | 1 | OV: 100% |

| Botanical family | Scientific name | Source | Life-form | Edible part | UR | UV | NU | FL |

| Malvaceae | Corchorus capsularis L. | C | Herb | Leaf and shoot | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | G: 100% |

| Malvaceae | Theobroma cacao L. | C | Tree | Fruit | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Meliaceae | Dysoxylum parasiticum (Osbeck) Kosterm. | C | Tree | Fruit | 25 | 0.25 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Meliaceae | Sandoricum koetjape (Burm.f.) Merr. | C | Tree | Fruit | 4 | 0.04 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Moraceae | Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. | C | Tree | Fruit | 64 | 0.64 | 2 | OV: 100%; OF: 100% |

| Moraceae | Artocarpus odoratissimus Blanco | C | Tree | Fruit | 12 | 0.12 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Moringaceae | Moringa oleifera Lam. | C | Shrub | Leaf | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | G: 100% |

| Musaceae | Musa sp. | C | Herb | Fruit | 136 | 1.36 | 2 | W: 100%; OF: 100% |

| Myrtaceae | Psidium guajava L. | C/W | Tree | Fruit | 25 | 0.25 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Myrtaceae | Syzygium samarangense (Blume) Merr. and L.M.Perry | C | Tree | Fruit | 4 | 0.04 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Myrtaceae | Syzygium aqueum (Burm.f.) Alston | C | Tree | Fruit | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Phyllanthaceae | Breynia androgyna (L.) Chakrab. & N.P.Balakr. | C | Shrub | Leaf | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | G: 100% |

| Poaceae | Oryza sativa L. | C | Herb | Seed | 15 | 0.15 | 1 | C: 100% |

| Poaceae | Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf | C | Herb | Leaf | 10 | 0.10 | 1 | S: 100% |

| Poaceae | Coix lacryma-jobi L. | C | Herb | Seed | 6 | 0.06 | 2 | C: 100%; S: 100% |

| Poaceae | Saccharum officinarum L. | C | Herb | Stem | 3 | 0.03 | 1 | S: 100% |

| Poaceae | Zea mays L. | C | Herb | Seed | 79 | 0.79 | 1 | C: 100% |

| Rubiaceae | Coffea canephora Pierre ex A.Froehner | C | Shrub | Seed | 48 | 0.48 | 1 | S: 100% |

| Rutaceae | Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr. | C | Tree | Fruit | 16 | 0.16 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Rutaceae | Citrus × aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle | C | Tree | Fruit | 9 | 0.09 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Rutaceae | Citrus × aurantium L. | C | Tree | Fruit | 2 | 0.02 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Rutaceae | Citrus × microcarpa Bunge | C | Shrub | Fruit | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Salicaceae | Pangium edule Reinw. | W | Tree | Fruit | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Sapindaceae | Nephelium lappaceum L. | C | Tree | Fruit | 9 | 0.09 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Sapotaceae | Chrysophyllum cainito L. | C | Tree | Fruit | 7 | 0.07 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Solanaceae | Solanum americanum Mill. | W | Herb | Leaf and shoot | 17 | 0.17 | 1 | G: 100% |

| Solanaceae | Solanum melongena L. | C | Herb | Fruit | 11 | 0.11 | 1 | OV: 100% |

| Solanaceae | Solanum aethiopicum L. | C | Herb | Fruit | 9 | 0.09 | 1 | OV: 100% |

| Solanaceae | Capsicum annuum L. | C | Herb | Fruit, leaf, and shoot | 15 | 0.15 | 3 | VA: 100%; G: 50%; S: 100% |

| Solanaceae | Solanum lycopersicum L. | C | Herb | Fruit | 2 | 0.02 | 1 | OV: 100% |

| Solanaceae | Solanum tuberosum L. | C | Herb | Tuber | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | W: 100% |

| Zingiberaceae | Amomum muricarpum Elm. | W | Herb | Fruit | 6 | 0.06 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Zingiberaceae | Etlingera elatior (Jack) R.M.Sm. | W | Herb | Inflorescence | 6 | 0.06 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Zingiberaceae | Hornstedtia conoidea Ridl. | W | Herb | Fruit | 6 | 0.06 | 1 | OF: 100% |

| Zingiberaceae | Zingiber officinale Roscoe | C | Herb | Rhizome | 4 | 0.04 | 1 | S: 100% |

| Zingiberaceae | Curcuma longa L. | C | Herb | Rhizome | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | S: 100% |

| Zingiberaceae | Hornstedtia lophophora Ridl. | W | Herb | Fruit | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | OF: 100% |

Table 4

Comparison of knowledge for edible plant species between males and females in the Higaonon tribe."

| Knowledge about edible plant species | Gender | Mean | SD | SEM | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of reported edible plant species | Female | 9.38 | 3.60 | 0.42 | 0.000 |

| Male | 13.19 | 4.78 | 0.94 | ||

| Number of reported edible plant species collected from farm | Female | 6.36 | 3.18 | 0.37 | 0.383ns |

| Male | 7.00 | 3.16 | 0.62 | ||

| Number of reported edible plant species collected from homegarden | Female | 2.78 | 2.57 | 0.30 | 0.529ns |

| Male | 3.19 | 3.49 | 0.68 | ||

| Number of reported edible plant species collected from communal area | Female | 0.38 | 1.00 | 0.12 | 0.022 |

| Male | 1.42 | 2.12 | 0.42 | ||

| Number of reported edible plant species collected from forest | Female | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.010 |

| Male | 2.08 | 3.72 | 0.73 | ||

| Number of reported edible plant species collected from river bank | Female | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.556ns |

| Male | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Table 5

Comparison of knowledge for edible plant species associated with different collection sites in the 5 villages of the Higaonon tribe."

| Source of variation | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F-value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of edible plant species in 5 villages | Between villages | 54.87 | 4 | 13.717 | 0.748 | 0.562ns |

| Within village | 1742.44 | 95 | 18.342 | |||

| Total | 1797.31 | 99 | - | |||

| Farm | Between villages | 54.59 | 4 | 13.648 | 1.376 | 0.248ns |

| Within village | 942.32 | 95 | 9.919 | |||

| Total | 996.91 | 99 | - | |||

| Homegarden | Between villages | 83.71 | 4 | 20.927 | 2.816 | 0.029 |

| Within village | 706.08 | 95 | 7.432 | |||

| Total | 789.79 | 99 | - | |||

| Communal area | Between villages | 5.32 | 4 | 1.330 | 0.627 | 0.644ns |

| Within village | 201.43 | 95 | 2.120 | |||

| Total | 206.75 | 99 | - | |||

| Forest | Between villages | 32.86 | 4 | 8.214 | 1.972 | 0.105ns |

| Within village | 395.65 | 95 | 4.165 | |||

| Total | 428.51 | 99 | - | |||

| River bank | Between villages | 0.05 | 4 | 0.013 | 1.330 | 0.264ns |

| Within village | 0.94 | 95 | 0.010 | |||

| Total | 0.99 | 99 | - |

Table 6

Nutrient compositions of the selected staple crops as alternative and/or supplemental food sources to rice."

| Rice | Corn grits | Cassava | Yautia | Sweet potato (yellow variety) | Banana | Taro | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition | |||||||

| Energy (kcal) | 129 | 350 | 111 | 122 | 128 | 159 | 105 |

| Protein (g) | 2.1 | 7.7 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| Total fat (g) | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.1 |

| Total carbohydrate (g) | 29.7 | 78.1 | 27.1 | 29.4 | 30.7 | 38.6 | 24.4 |

| Minerals | |||||||

| Calcium (mg) | 11 | 22 | 10 | 38 | 30 | 19 | 37 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 36 | 213 | 22 | 53 | 26 | 37 | 41 |

| Iron (mg) | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.7 |

| Sodium (mg) | 3 | 1 | 4 | 24 | 43 | 2 | 11 |

| Fat-soluble vitamins | |||||||

| β-carotene (µg) | 0 | 65 | 0 | 0 | 280 | 170 | 5 |

| RAE (µg) | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 14 | 0 |

| Water-soluble vitamins | |||||||

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Vitamin B2 (mg) | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Niacin (mg) | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 0 | 0 | 22 | 5 | 14 | 25 | 6 |

| [1] | Abeto, R., Calilung, Z., Talubo, J.P., et al., 2004. Community mapping in the Philippines:a case study on the ancestral domain claim of the Higa-onons in Impasug-ong, Bukidnon. In: Regional Community Mapping Network Workshop. Quezon: Philippine Association for Intercentural Development, 1-7. |

| [2] |

Angeles-Agdeppa, I., Denney, L., Toledo, M.B., 2019. Inadequate nutrient intakes in Filipino schoolchildren and adolescents are common among those from rural areas and poor families. Food Nutr. Res. 633435, doi: 10.29219/fnr.v63.3435.

doi: 10.29219/fnr.v63.3435 |

| [3] |

Angeles-Agdeppa, I., Sun, Y., Tanda, K.V., 2020. Dietary pattern and nutrient intakes in association with non-communicable disease risk factors among Filipino adults: a cross-sectional study. Nutr. J. 19(79), doi: 10.1186/s12937-020-00597-x.

doi: 10.1186/s12937-020-00597-x |

| [4] | Antonelli, A., Fry, C., Smith, R.J., et al., 2020. State of the World’s Plants and Fungi 2020. [2021-08-20]. https://www.kew.org/science/state-of-the-worlds-plants-and-fungi. |

| [5] | Baja-Lapis, A.C., 2010. A Field Guide to Philippine Rattans. Masaya: Asia Life Sciences, 1-124. |

| [6] |

Baldermann, S., Blagojević, L., Frede, K., et al., 2016. Are neglected plants the food for the future ? Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 35(2), 106-119.

doi: 10.1080/07352689.2016.1201399 |

| [7] | Blesh, J., Hoey, L., Jones, A.D., et al., 2019. Development pathways toward “zero hunger”. World Dev. 118, 1-14. |

| [8] |

Borelli, T., Hunter, D., Padulosi, S., et al., 2020. Local solutions for sustainable food systems: the contribution of orphan crops and wild edible species. Agronomy. 10(2), 231, doi: 10.3390/agronomy10020231.

doi: 10.3390/agronomy10020231 |

| [9] | Buenavista, D.P., Wynne-Jones, S., McDonald, M., 2018. Asian indigeneity, indigenous knowledge systems, and challenges of the 2030 agenda. East Asian Community Review. 1, 221-240. |

| [10] | Buenavista, D.P., 2021. Co-production of knowledge with indigenous peoples for UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):Higaonon Food ethnobotany, and a discovery of a new Begonia species in Mindanao, Philippines. PhD Dissertation. Bangor: Bangor University. |

| [11] |

Buenavista, D.P., Dinopol, M.A., Mollee, E., et al., 2021. From poison to food: on the molecular identity and indigenous peoples’ utilisation of poisonous “Lab-o” (Wild Yam, Dioscoreaceae) in Bukidnon, Philippines. Cogent Food Agr. 7(1), doi: 10.1080/23311932.2020.1870306.

doi: 10.1080/23311932.2020.1870306 |

| [12] | Bukidnon-Higaonon Community of Malabalay City, Bukidnon for the Department of Environment, Natural Resources and the Asian Development Bank, 2019. PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project: Higaonon Ancestral Domain. [2021-07-26]. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-documents/41220/41220-013-ipp-en_8.pdf. |

| [13] |

Bvenura, C., Afolayan, A.J., 2015. The role of wild vegetables in household food security in South Africa: A review. Food Res. Int. 76(4), 1001-1011.

doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2015.06.013 |

| [14] | Camacho, L.D., Gevaña, D.T., Carandang, A.P., et al., 2016. Indigenous knowledge and practices for the sustainable management of Ifugao forests in Cordillera, Philippines. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management. 12(1-2), 5-13. |

| [15] | Camou-Guerrero, A., Reyes-García, V., Martínez-Ramos, M., et al., 2008. Knowledge and use value of plant species in a Rarámuri community: A gender perspective for conservation. Hum. Ecol. 36, 259-272. |

| [16] | Capanzana, M.V., Aguila, D.V., 2020. Philippines case study:government policies on nutrition education. In: Black, M.M., Delichatsios, H.K., Story, M.T., (eds.). Nutrition Education:Strategies for Improving Nutrition and Healthy Eating in Individuals and Communities. Geneva: NestléNutrition Institute Workshop Series, 119-130. |

| [17] | Chiong-Javier, M.E., 2012. Gendered networks, social capital, and farm women’s narket participation in Southern Philippines. In: Maraan, C.J., (ed.). Holding Their Own:Smallholder Production, Marketing and Women Issues in Philippine Agroforestry. Manila:Social Development Research Center, De La Salle University, 54-84. |

| [18] | Cole, F.C., Martin, P.S., Ross, L.A., 1956. The Bukidnon of Mindanao. Chicago: Chicago Natural History Museum Press, 51-56. |

| [19] | Cullen, V.G., 1979. Social change and religion among the Bukidnon. Philippine Studies. 27(2), 160-175. |

| [20] | Dawe, D., Moya, P.F., Casiwan, C.B., 2006. Why does the Philippines import rice? Meeting the challenge of trade liberalization. Manila: International Rice Research Institute, 1-7. |

| [21] | Dawe, D., 2010. The Rice Crisis: Markets, Policies and Food Security (1st edition). London: Routledge, 3-15. |

| [22] |

Del-Castillo, Á.M.R., Gonzalez-Aspajo, G., de Fátima Sánchez-Márquez, M., et al., 2019. Ethnobotanical Knowledge in the Peruvian Amazon of the Neglected and Underutilized Crop Sacha Inchi (Plukenetia volubilis L.). Econ. Bot. 73(2), 281-287.

doi: 10.1007/s12231-019-09459-y |

| [23] | dela Cruz, E., 2020a. Philippines plans rice imports to boost stocks for coronavirus fight. [2021-07-20]. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-philippines-rice-idUSKBN21I0DU. |

| [24] | dela Cruz, E., 2020b. More than half of Philippines’ 2020 rice import orders yet to be delivered-minister. [2021-08-20]. https://www.zawya.com/en/business/more-than-half-of-philippines-2020-rice-import-orders-yet-to-be-delivered-minister-mj7f361c. |

| [25] | dela Cruz, E., 2021. Philippines sees 2021 minimum rice import requirement at 1.69mln T. [2021-06-29]. https://www.agriculture.com/markets/newswire/philippines-sees-2021-minimum-rice-import-requirement-at-169-mln-t. |

| [26] | Department of Science and Technology-Food and Nutrition Research Institute of Republic of the Philippines, 2015. 8th National Nutrition Survey. [2021-06-15]. https://www.fnri.dost.gov.ph/index.php/tools-and-standard/nutritional-guide-pyramid/19-nutrition-statistic/118-8th-national-nutrition-survey. |

| [27] |

Edgerton, R.K., 1983. Social disintegration on a contemporary Philippine frontier: the case of Bukidnon, Mindanao. J. Contemp. Asia. 13(2), 151-175.

doi: 10.1080/00472338380000111 |

| [28] |

Ferguson, M., Brown, C., Georga, C., et al., 2017. Traditional food availability and consumption in remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory, Australia. Aust. N. Z. Publ. Health. 41(3), 294-298.

doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12664 |

| [29] | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 1999 Use and Potential of Wild Plants in Farm Households. Rome: FAO, 1-2. |

| [30] | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), et al., 2020. In Brief to the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets. [2021-07-05]. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/nutritionlibrary/publications/state-food-security-nutrition-2020-inbrief-en.pdf?sfvrsn=65fbc6ed_4. |

| [31] | Friedman, J., Yaniv, Z., Dafni, A., et al., 1986. A preliminary classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants, based on a rational analysis of an ethnopharmacological field survey among Bedouins in the Negev Desert, Israel. J. Ethnopharmacol. 16(2-3), 275-287. |

| [32] |

Gatto, M., Naziri, D., San Pedro, J., et al., 2021. Crop resistance and household resilience—the case of cassava and sweetpotato during super-typhoon Ompong in the Philippines. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 62, 102392, doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102392.

doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102392 |

| [33] | Ghosh-Jerath, S., Singh, A., Lyngdoh, T., et al., 2018. Estimates of indigenous food consumption and their contribution to nutrient entake in Oraon Tribal women of Jharkhand, India. Food Nutr. Bull. 39(47), 581-594. |

| [34] |

Ghosh-Jerath, S., Kapoor, R., Singh, A., et al., 2020. Leveraging traditional ecological knowledge and access to nutrient-rich indigenous foods to help achieve SDG 2: an analysis of the indigenous foods of Sauria Paharias, a vulnerable tribal community in Jharkhand, India. Front. Nutr. 7, 61, doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.00061.

doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.00061 |

| [35] | Giraldi, M., Hanazaki, N., 2014. Use of cultivated and harvested edible plants by Caiçaras—what can ethnobotany add to food security discussions? Hum. Ecol. Rev. 20(2), 51-73. |

| [36] | Grune, T., Lietz, G., Palou, A., et al., 2010. β-carotene is as an important vitamin A source for humans. J. Nutr. 140(12), 2268-2285. |

| [37] |

Hagen, R., van der Ploeg, J., Minter, T., 2016. How do hunter-gatherers learn? The transmission of indigenous knowledge among the Agta of the Philippines. Hunter Gatherer Research. 2(4), 389-413.

doi: 10.3828/hgr.2016.27 |

| [38] | Hegazy, A.K., Hosni, H.A., Lovett-Doust, L., et al., 2020. Indigenous knowledge of wild plants collected in Darfur, Sudan. A Journal of Plants, People, and Applied Research-Ethnobotany Research & Applications. 19(47), 1-19. |

| [39] |

Heineberg, M.R., Hanazaki, N., 2019. Dynamics of the botanical knowledge of the Laklãnõ-Xokleng indigenous people in Southern Brazil. Acta Bot. Bras. 33(2), doi: 10.1590/0102-33062018abb0307.

doi: 10.1590/0102-33062018abb0307 |

| [40] | Huesca, E.F., 2016. Plantation economy, indigenous people, and precariousness in the Philippine Uplands:the Mindanao experience. In: Carnegie, P., King, V., Zawawi, I., (eds.). Human Insecurities in Southeast Asia, Asia in Transition. Singapore: Springer, 173-192. |

| [41] | Hunter, D., Borelli, T., Beltrame, D.M.O., et al., 2019. The potential of neglected and underutilized species for improving diets and nutrition. Planta. 250, 709-729. |

| [42] | Imbong, J.D., 2021. “Bungkalan” and the Manobo-Pulangihon tribe’s resistance to corporate land-grab in Bukidnon, Mindanao. Alternative. 17(1), 23-31. |

| [43] | Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), 2018. The IPBES Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for Asia and the Pacific. Bonn: IPBES, 13-14. |

| [44] | Kennedy, G., Ballard, T., Dop, M., 2010. Guidelines for Measuring Household and Individual Dietary Diversity. Rome: FAO, 37-49. |

| [45] | Kuhnlein, H.V., 2009. Why are indigenous peoples’ food systems important and why do they need documentation? In: Indigenous Peoples’ Food Systems: The Many Dimensions of Culture, Diversity and Environment for Nutrition and Health. Rome: FAO, 3-8. |

| [46] | Lao, M.M., 1987. The economy of the Bukidnon Plateau during the American period. Philippine Studies. 35(3), 316-331. |

| [47] |

Lin, B.X., Zhang, Y.Y., 2020. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on agricultural exports. J. Integr. Agric. 19(12), 2937-2945.

doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(20)63430-X |

| [48] | Lynch, F., 1967. The Bukidnon of north-central Mindanao in 1889. Philippine Studies. 15(3), 464-482. |

| [49] | Mustafa, M.A., Mayes, S., Massawe, F., 2019. Crop diversification through a wider use of underutilised crops:a strategy to ensure food and nutrition security in the face of climate change. In: Sarkar, A., Sensarma, S., van Loon, G., (eds.). Sustainable Solutions for Food Security. Cham: Springer, 125-149. |

| [50] |

Narciso, J.O., Nyström, L., 2020. Breathing new life to ancient crops: Promoting the ancient Philippine grain “Kabog Millet” as an alternative to rice. Foods. 9, 1727, doi: 10.3390/foods9121727.

doi: 10.3390/foods9121727 |

| [51] | Ollitrault, P., Navarro, L., 2012. Citrus. In: Badenes, M.L., Byrne, D.H., (eds.). Fruit Breeding, Handbook of Plant Breeding 8. Boston: Springer, 623-662. |

| [52] | Padulosi, S., Thompson, J., Rudebjer, P., 2013. Fighting Poverty, Hunger and Malnutrition with Neglected and Underutilized Species (NUS): Needs, Challenges and the Way Forward. Rome: Biodiversity International, 1-19. |

| [53] | Philippine Statistics Authority, 2010. A Filipino Family Consumed 8.9 kg of Ordinary Rice a Week in 2006 (Results from the 2006 Family Income and Expenditure Survey (FIES)). [2021-08-12]. https://psa.gov.ph/content/filipino-family-consumed-89-kg-ordinary-rice-week-2006-results-2006-family-income-and. |

| [54] | Philippine Statistics Authority, 2018. 2017 Commodity Fact Sheets. [2021-08-14]. https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/CommodityFactSheets_2017.pdf. |

| [55] | Phillips, O.L., Gentry, A.H., 1993. The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru: I. statistical hypotheses tests with a new quantitative technique. Econ. Bot. 47, 15-32. |

| [56] |

Pieroni, A., Sõukand, R., Bussmann, R.W., 2020. The inextricable link between food and linguistic diversity: wild food plants among diverse minorities in Northeast Georgia, Caucasus. Econ. Bot. 74(4), 379-397.

doi: 10.1007/s12231-020-09510-3 |

| [57] | Poffenberger, M., McGean, B., (eds.). 1993. Upland Philippine Communities: Guardians of the Final Forest Frontiers. Berkeley: Center for Southeast Asian Studies of University of California, 27-34. |

| [58] | Prance, G.T., Balée, W., Boom, B.M., et al., 1987. Quantitative ethnobotany and the case for conservation in Amazonia. Conserv. Biol. 1(4), 296-310. |

| [59] |

Quave, C.L., Pieroni, A., 2015. A reservoir of ethnobotanical knowledge informs resilient food security and health strategies in the Balkans. Nat. Plants. 1, 14021, doi: 10.1038/nplants.2014.21.

doi: 10.1038/nplants.2014.21 |

| [60] |

Rachkeeree, A., Kantadoung, K., Suksathan, R., et al., 2018. Nutritional compositions and phytochemical properties of the edible flowers from selected Zingiberaceae found in Thailand. Front. Nutr. 5(3), doi: 10.3389/fnut.2018.00003.

doi: 10.3389/fnut.2018.00003 |

| [61] |

Rolnik, A., Olas, B., 2020. Vegetables from the Cucurbitaceae family and their products: Positive effect on human health. Nutrition. 78, 110788, doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2020.110788.

doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2020.110788 |

| [62] |

Samuels, J., 2015. Biodiversity of food species of the Solanaceae family: a preliminary taxonomic inventory of subfamily Solanoideae. Resources. 4(2), 277-322.

doi: 10.3390/resources4020277 |

| [63] | Sarkar, D., Walker-Swaney, J., Shetty, K., 2020. Food diversity and indigenous food systems to combat diet-linked chronic diseases. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 4(Suppl. 1), 3-11. |

| [64] | Sealza, I.S., 1984. From staple to cash crop: a survey study of the plantation industry and occupational diversification in Bukidnon Province. Philippine Sociological Review. 32(1/4), 91-104. |

| [65] | Singh, A.B., Teron, R., 2017. Ethnic food habits of the Angami Nagas of Nagaland state, India. Int. Food Res. J. 24(3), 1061-1066. |

| [66] |

Spencer, J.E., 1975. The rise of maize as a major crop plant in the Philippines. J. Hist. Geogr. 1(1), 1-16.

doi: 10.1016/0305-7488(75)90071-7 |

| [67] | Strobel, M., Tinz, J., Biesalski, H.K., 2007. The importance of β-carotene as a source of vitamin A with special regard to pregnant and breastfeeding women. Eur. J. Nutr. 46(Suppl. 1), 1-20. |

| [68] |

Termote, C., van Damme, P., Djailo, B.D., 2011. Eating from the wild: Turumbu, Mbole and Bali traditional knowledge on non-cultivated edible plants, District Tshopo, DRCongo. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 58, 585-618.

doi: 10.1007/s10722-010-9602-4 |

| [69] |

Thakur, D., Sharma, A., Uniyal, S.K., 2017. Why they eat, what they eat: patterns of wild edible plants consumption in a tribal area of Western Himalaya. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 13, 70, doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0198-z.

doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0198-z |

| [70] |

Turner, S., 2012. Making a living the Hmong way: an actor-oriented livelihoods approach to everyday politics and resistance in upland Vietnam. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 102(2), 403-422.

doi: 10.1080/00045608.2011.596392 |

| [71] |

Turreira-García, N., Theilade, I., Meilby, H., et al., 2015. Wild edible plant knowledge, distribution and transmission: a case study of the Achí Mayans of Guatemala. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 11(52), doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0024-4.

doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0024-4 |

| [72] | Ulian, T., Diazgranados, M., Pironon, S., et al., 2020. Unlocking plant resources to support food security and promote sustainable agriculture. Plants People Planet. 2, 421-445. |

| [73] | United Nations (UN), 2015. Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations, 1-35. |

| [74] | Whitney, C.W., 2021. EthnobotanyR: calculate quantitative ethnobotany indices. [2021-08-18]. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ethnobotanyR/ethnobotanyR.pdf. |

| [75] |

Yang, J.B., Wang, Y.C., Wang, D., et al., 2018. Application of traditional knowledge of Hani people in biodiversity conservation. Sustainability. 10(12), 4555, doi: 10.3390/su10124555.

doi: 10.3390/su10124555 |

| [1] | Birgit Anika RUMPOLD, SUN Lingxiao, Nina LANGEN, YU Ruide. A cross-cultural study of sustainable nutrition and its environmental impact in Asia and Europe: A comparison of China and Germany [J]. Regional Sustainability, 2024, 5(2): 100136-. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||

REGSUS Wechat

REGSUS Wechat

新公网安备 65010402001202号

新公网安备 65010402001202号